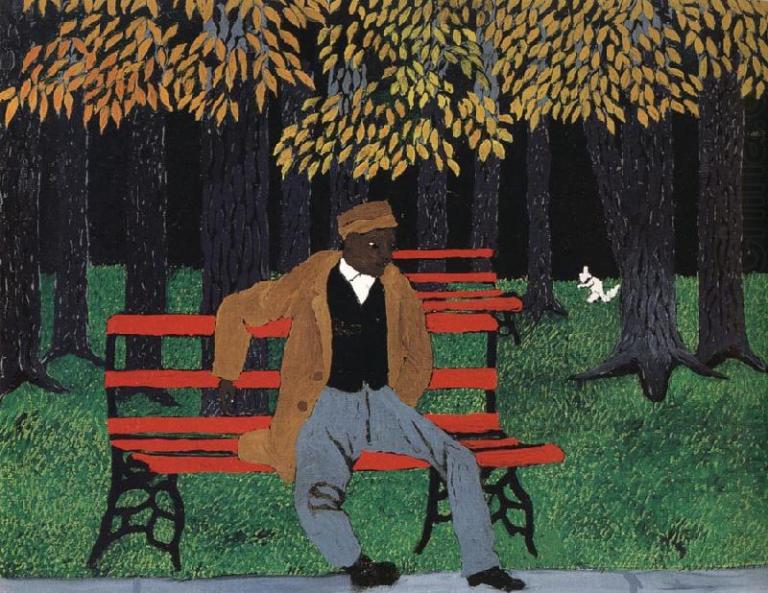

In I Tell My Heart: The Art of Horace Pippin. Philadelphia: Pennsylvania Academy of the Arts, 1993

Pictures just come to my mind, and I tell my heart to go ahead.

—HORACE PIPPIN

BETWEEN 1930 AND 1950, the question of what constituted the authentic expression of the American spirit in the visual arts was answered in several ways. In the thirties, the native-scene painters who celebrated the nation’s regional landscape were acclaimed as the best examples of indigenous talent. Beginning in the late forties, those artists newly identified as Abstract Expressionists were thought best to embody essential American values. Yet between the heyday of the Regionalists and the ascendancy of the Action Painters, the richly varied category of unschooled art was regarded by many as most representative of the American character.

In an essay accompanying Horace Pippin’s first solo show in Philadelphia in January 1940, the well-known art collector Dr. Albert C. Barnes described his work as having “the individual savor of its soil: Pippin’s art is distinctly American; [in] its ruggedness, vivid drama, stark simplicity, picturesqueness and accentuated rhythms.” That Pippin was an African American was a factor that underscored the uniqueness of his contribution. To Barnes, Pippin’s paintings “have their musical counterparts in the Spirituals of the American Negro.” Labeling Pippin as “the first important Negro painter to appear on the American scene,” Barnes awarded him and the self-taught painter John Kane the distinction of creating “the most individual and unadulterated painting authentically expressive of the American spirit that has been produced in our generation.” Who was Horace Pippin? How did the disabled World War I veteran emerge from obscurity to a position of prominence in the history of twentieth-century American painting?

Horace Pippin was born in West Chester, Pennsylvania, on Washington’s birthday, 1888. Because of the poor record keeping of that time, the exact circumstances of his birth are today unknown. In answer to a biographical questionnaire during his lifetime, Pippin listed his mother as Harriet Johnson Pippin and his father as Horace Pippin. Selden Rodman and Carole Cleaver’s 1972 book on Pippin cites his mother as Christine Pippin (1855-1925), a domestic servant born in Charleston, West Virginia, who was the daughter of Harriet Irwin Pippin (1834-1908). Harriet Pippin’s obituary notice in the Goshen, New York Independent Republican, named three children, including a daughter Christine and a son Horace.1 Whether Harriet, who was listed as a widow of 45 years in the census of 1880, was Pippin’s birth mother, or was his de facto mother cannot be determined. The ages given for nineteenth-century census purposes are well-known to be estimates. In 1891 the Pippin family moved to the resort town of Goshen, New York. Christine worked as a domestic servant outside the home, while Harriet likely cared for Horace. Christine later married Benedict Green with whom she had four daughters. As a boy, Horace showed a strong interest in drawing, winning his first set of crayons and a box of watercolors for his response to an advertising contest by an art-supply company. Goshen was home to a celebrated harness race track, and as a youngster Pippin made drawings of the horses and drivers. He attended a segregated one-room school house until 1902, when at age fourteen, he left to help support the family. Harriet Pippin died in 1908, and by 1912 Pippin had relocated to Paterson, New Jersey. Here he worked for a moving-and-storage company, where he relished the task of crating oil paintings, which first exposed him to fine art. Prior to 1917, Pippin variously toiled in a coal yard, in an iron foundry, as a hotel porter, and as a used clothing peddler.

To Horace Pippin, World War I “brought out all the art in me.”2 In 1917 the twenty-nine-year-old Pippin enlisted in the Fifteenth Regiment of the New York National Guard, serving as a corporal in what would subsequently become the 369th Colored Infantry Regiment of the guard Division of the United States Army. Landing in Brest in December 1917, Pippin and his regiment first worked laying railroad track prior to serving at the front lines in the Argonne Forest under French command. While in the trenches, Pippin kept illustrated journals of his military service. Only six drawings from this period survive. In October 1918, a German sniper shot Pippin through the right shoulder. The future painter was honorably discharged the following year, after fourteen months of service. Along with all the men in his regiment, Pippin earned the French Croix de Guerre in 1919. Twenty-six years later he applied for a Purple Heart, awarded retroactively in 1945.

In 1920, Pippin married the twice-widowed Jennie Fetherstone Wade Giles, who was four years older than the artist and had a six-year-old son. Supporting themselves on his disability check and her work as a laundress, they settled in West Chester, Pennsylvania, where Jennie owned a home with a pleasant garden. By 1940 they would proudly note to a reporter from Time that they “have turkey for Christmas, goose for New Year’s and guinea fowl for their birthdays.”3 A community-spirited man, Pippin helped organize a black Boy Scout troop and a drum-and-bugle corps for the local American I legion post for black veterans, for which he also served as a commander. A reporter for the Baltimore Afro-American newspaper described him as “a big, genial man, plain in speech and in manner.. . . His sense of humor is subtle and provocative and [he] is profoundly religious.”4 The artist Romare Bearden, who once met Pippin at New York’s Downtown Gallery, where they both showed their work, found Pippin’s self commentary on his art to be animated and “very humorous.”5 In 1941 another journalist characterized Pippin as “a tall, open-faced man [who] smiles often and has a loud, unrestrained, hearty laugh.”6 Claude Clark, an African-American painter who knew Pippin in the forties, said that the artist reminded him of John Henry, the steel-driving hero of American folk song.7 Another black artist, Edward Loper, also knew Pippin in the forties and once commented on the formative influence of the war on Pippin’s demeanor:

At that time there were certain kinds of black men who I admired and they were the kind of black guys who I think came out of the first world war. They had self respect and [Pippin] had lots of self respect. He knew he was strong. To me he was the kind of black man who wouldn’t take too much smart alecky stuff from other people. Other people knew he wouldn’t do that so they didn’t try it with him.8

As therapy for his injured right arm, which he could not raise above shoulder height, Pippin began using charcoal to decorate discarded cigar boxes. He would later tell a reporter: “the boxes were pretty, but I was not satisfied with them.”9 When, in 1925, he began burning images on wood panels using a hot iron poker, he was delighted with the results: “It brought me back to my old self.” Neighbors recall that Pippin enjoyed whittling and crafting decorative picture frames and jewelry boxes.10 In 1928, at the age of forty, he expanded to oil paints, completing his first painting The End of the War: Starting Home in 1930. In a first-floor parlor, he painted by using his left hand to prop up his right forearm. Because his disability made it difficult for him to work on a large scale, his paintings rarely exceeded 25 x 30 inches. At various points in his subsequent artistic career, Pippin made preparatory pencil sketches for his compositions, some of which are extant. Claude Clark recalled that “When [Pippin] was doing the John Brown series he showed me the drawings [made] when he had gone to the courthouse of the period and noticed that they had a desk where they had a compartment where they kept their scrolls. And he made detailed drawings of this.”11

Although Pippin worked on a variety of paintings and burnt-wood panels during the twenties and most of the thirties, his activities as an artist were unknown beyond his immediate circle of friends and family. To some of the shopkeepers in West Chester whose businesses he patronized, Pippin offered paintings in lieu of payment. Several shops informally displayed his work. Devere Kauffman recalls that sometime before the war, his family’s furniture store, Kauffman’s, agreed to exhibit a group of Pippin’s small paintings that the artist had brought in to show them. The artwork was priced at fifteen dollars each and was installed in the listening booth area of their phonograph department. According to Kauffman, the only person who responded positively to the paintings was a Miss Scott, the head of the art department of what was then called the West Chester State Teachers College.12 Another instance of Pippin’s interactions with his community regards his barber, who, it was said, kept The Buffalo Hunt (1933) in his shop because his wife didn’t want it in her home. When the work was borrowed back for Pippin’s second show in Philadelphia and subsequently sold for $150 to the Whitney Museum in 1941, the barber reportedly was incredulous.13

Over fifty years after his death, it is not possible to pinpoint accurately how Pippin made the transition from obscurity to public notice within the West Chester community. Several versions have emerged that have in common the catalytic role of Chester County resident Christian Brinton (1871-1942), an “author, editor, impresario, critic, and collector [who] delighted in discovering fresh talent.”14 In 1988, high school students in an American history seminar at West Chester’s Henderson High School created a self-published study on Pippin based in part on interviews with members of the African-American community who knew the artist. Two new accounts of his “discovery” emerged.

Warren Burton, who was a teacher at West Chester’s Gay Street School, recalled that one day he made a house visit to meet the parents of his eighth-grade student Richard Wade, Pippin’s stepson. After seeing the artist at work at his easel in the dining room, he shared news of his discovery with the school’s principal, Joseph Fugett, who reportedly contacted his friend, the critic Christian Brinton.15 It is interesting to note that in 1938 Pippin presented the Fugett family with one of his works, an unfinished painting entitled On Guard, a gesture that bespeaks the artist’s esteem and appreciation.16

A second account cited by the students in 1988 came from an interview taped prior to 1983, when West Chester artist Philip Jamison recorded his talk with teacher London Jones, a friend of Pippin’s. Occasionally, Mr. Jones would help out at his sister-in-law Sarah Spangler’s restaurant, where one of Pippin’s paintings was on display. The interviewee could not recollect definitively whether Christian Brinton was the “small white fella” who ordered “a tomato and lettuce sandwich and a cup of tea,” but the man was sufficiently taken with the painting to press Jones to arrange a meeting with the painter. When Jones phoned him, Pippin reportedly exclaimed, “He must be an artist. He knows a good painting when he sees it.”17According to Jones, the artist and the critic met as a result of his intervention and Pippin agreed to enter two works in a local art show.

The canonical account of Pippin’s breakthrough also involves a West Chester shop. In the spring of 1937, Pippin placed two small framed paintings—The Moose I (1936) and Cabin in the Cotton I (1935)—in the window of a shoe-repair store. Each was priced at five dollars. George H. Straley, then a cub reporter for West Chester’s Daily Local News, happened on the paintings and was intrigued enough to call them to the attention of Christian Brinton,18 then president of the Chester County Art Association (CCAA). According to Straley, Brinton came to see them a few days later with the well-known artist and illustrator N. C. Wyeth, vice president of the art association. These two luminaries may have convinced Pippin to submit his work to the upcoming “Sixth Annual Exhibition” of the CCAA, scheduled to run from May 23 to June 6, or possibly Pippin applied on his own initiative.

But the oft-told tale of Christian Brinton’s support may not be fully accurate. True, Horace Pippin was first African American to have sent pictures to the art association’s sixth annual event. But according to N. C. Wyeth’s daughter, Ann Wyeth McCoy, an apprehensive Brinton was in charge of assembling and installing all submissions. He sought to minimize any adverse reaction to Pippin’s presence by hanging the artist’s two canvases in a remote section of the top floor. Indeed, the exhibition catalogue lists both of Pippin’s paintings, Cabin in the Cotton I and The Blue Tiger (1933), as hanging in the “upper hallway.” When artist John McCoy, who was chairman of the hanging committee, saw the works, he proclaimed them “beautiful . . . the best things in the show,” and prevailed on Brinton to rehang at least one in a more prominent location. McCoy then brought in his father-in-law, N. C. Wyeth (chairman of the jury of selection and award), who persuaded Brinton to arrange a one-man show for Pippin as soon as the current exhibition ended.19

The art association’s two-week show attracted a record 2,550 people, according to the Daily Local News, “the greatest number of visitors of any local modern show of contemporary paintings on record.”20 That the Chester County Art Association drew upon an unusually talented group of exhibitors is evidenced by the 1937 prize winners. A jury of five, which included N. C. Wyeth; John Frederick Lewis, Jr.; and Dr. Henry C. Brinton, awarded a special mention to both of Pippin’s paintings. (First prize was given to the Belgian-born Franz de Merlier for his painting of William Worthington Tanguy,21 second to Andrew Wyeth for a portrait of the Chester County historian Christian C. Sanderson, and third prize to Ralston Crawford for a work entitled Section of a Steel Mill.) In a letter dated May 26,1937, Christian Brinton wrote to John Frederick Lewis, Jr., the philanthropist and vice president of the art association, that attendance was outstanding and that interest centered on the prize painting by Franz de Merlier and Pippin’s Cabin in the Cotton I.22 Despite any initial apprehension, Christian Brinton threw himself into raising exhibition funds and eliciting press support for Pippin. On June 1, Brinton wrote to an art association patron alerting him to the opening a week away, of “our negro artist discovery, Horace Pippin,” and added: “I had no difficulty in securing support for an appropriate catalogue of his work.”23 That same day Brinton wrote the Philadelphia Tribune, a black newspaper, about “our self-taught West Chester artistic discovery.” He enclosed a typed copy of the exhibition catalogue, then on press, and outlined the events planned for the opening.

That Brinton’s fears of a hostile response to Pippin’s works were not altogether unfounded is evidenced by an anonymous review in a local paper that was published after the show had been open for a week. The Coatesville Record’s “Market Scribe” first praised the contributions of the Wyeth and Hurd family of painters and then turned his attention to Pippin, described as “a West Chester negro, who never had any artistic training.” Of Pippin’s two works on view, he notes that “one can be dismissed without comment, but the other, so the judges say, has a ‘touch of genius.'” Yet the “Market Scribe” was unconvinced:

In producing this picture [Cabin in the Cotton] Pippin has violated just about every rule of good painting, but the result, despite all this, is something that has county art circles talking. Whether he can get the same effect again with another subject is a question. This may have been an accident and then again it may mean that this young man with proper training will go places. Only time will tell.24

Whether the reviewer was aware that Horace Pippin was close to fifty cannot be known. Regardless, the critic’s tone was deprecating and dismissive.

Two days following the close of the art association show, Pippin’s solo exhibition of ten paintings and seven burnt-wood panels opened at the West Chester Community Center, located on the other side of town. It was sponsored jointly by the center and the CCAA, and the opening ceremonies included talks by such local dignitaries as Christian Brinton, N. C. Wyeth, and Dr. Leslie Pinckney Hill, president of Cheyney State Teachers College. The future civil rights activist Bayard Rustin, then a student at Cheyney State, was a featured tenor soloist. It has long gone unnoted that the West Chester Community Center, located in the heart of the African-American community, was a hub for black cultural activity. The 1934 building that hosted Pippin’s works stood, in the words of a contemporary brochure, “as a lighthouse in the heart of the Negro residential area of West Chester.”25 Founded by the nearby Cheyney State Teachers College, an historically black institution, the West Chester Community Center had been incorporated in 1919 as an interracial organization “to provide facilities for the physical, social, moral and civic development of Negroes and to promote understanding and cooperation between the Races.” Various members of the African-American arts community were supportive of the center. For example, the painter Laura Wheeler Waring, an art instructor at Cheyney, served as an officer there in the 1940s. Well after he had achieved a national reputation, Pippin continued to exhibit at the center, sending two canvases to the second annual “Colored Artists of West Chester” exhibition held there in April 1945.26

Given the sophisticates of the white art association set, it is little wonder that news of Pippin’s “discovery” would spread rapidly beyond the confines of Chester County. On September 13,1937, Dorothy C. Miller, a curator at New York’s Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), wrote to Christian Brinton for information about Pippin and his work: “I have been told that you have sponsored an exhibition of paintings by a Negro ‘primitive’ or naive artist.”27 That Dorothy C. Miller described Pippin as a “primitive” reflects the common usage of the term in the twenties and the thirties to refer to artists with no formal training who were “creative by instinct,” in the words of the art historian who first applied the term to American paintings in 1923.28 Tellingly, a Philadelphia commentator on Pippin’s 1940 show at the Robert Carlen Gallery, noted: “What many an artist spends years learning, Pippin knows by instinct.”29 In Pippin’s day, the adjective “primitive,” which literally denoted the earliest stage or the beginning of things, was used to describe such diverse arenas as early American limners, French and Italian thirteenth-century painting, African art and artifacts, Northwest Coast Indian art, and contemporary unschooled artists.30

The benign art-world usage of such adjectives as “naive,” “primitive,” and “instinctive” notwithstanding, there is no question that the terms had racial overtones when employed by some commentators to describe Pippin. Periodically, Pippin’s admirers forged a connection between the artist’s life as an African American and the forthright, unselfconscious quality of his art. Dr. Barnes did so in 1940, when he described Pippin’s works as the musical counterparts of spirituals, and N. C. Wyeth did so in his remarks at the opening of Pippin’s 1937 exhibition at the West Chester Community Center. After noting that Pippin’s work “ought to be protected, cherished, and encouraged,” Wyeth remarked that it had “a basic African quality; the jungle is in it. It is some of the purest expression I have seen in a long time, and I would give my soul to be as naive as he is.”31 The feeling that Pippin’s art was pure, and therefore unsullied by the negative and artificial components of contemporary society, can be found again a decade later, in a review by a Philadelphia art critic: “The modern world admires Pippin because it is subconsciously jealous of the natural expression of a crude, simple soul. Pippin had something most of us have lost: something that was trained out of us.”32

According to his daughter Ann, N. C. Wyeth’s remarks about Pippin’s naivete should be seen in the context of his father’s career at that time. Wyeth, who was four years older than Pippin, had made his mark as an illustrator and teacher, but was nonetheless frustrated by the unequal recognition given to his own personal art work. The older artist, who died in 1945, a year before Pippin, remained a staunch advocate and admirer of the West Chester painter. In 1940 he wrote to Ann about Pippin’s response to her sister’s painting of a death mask of the poet Keats:

I had an astonishing time with Horace Pippin. I can’t possibly tell you about it adequately now: I’ll only tell you that after looking at many of mine, some of Andy’s [his son, Andrew Wyeth], and Henriette’s [his daughter], he looked at Carolyn’s [his daughter] Keats with real excitement and wonderment, blew a long low whistle and said, very slowly, and solemnly, “Now, that there’s a sensible picture!” It affected him deeply.33

Seven months after Dorothy C. Miller’s query, West Chester’s Daily Local News reported that Christian Brinton had sent ten of Pippin’s paintings to MoMA, and that four had been selected for inclusion in their 1938 exhibition “Masters of Popular Painting,” curated by Holger Cahill.34 It is telling that Pippin made his national debut at MoMA, which demonstrated its interest in folk art during the 1930s. For example, in 1932 Holger Cahill, then acting director, organized MoMA’s watershed exhibition of historical American painting and three-dimensional pieces entitled “American Folk Art: The Art of the Common Man, 1750-1900,” which firmly established the importance, quality, and diversity of indigenous American artistic expression.35 Two years earlier, while on the staff of the Newark Museum, Cahill had included the work of the living, self-taught artist Joseph Pickett from New Hope, Pennsylvania, in “American Primitives,” his exhibition of contemporary folk art. In Cahill’s catalogue introduction, he spoke of primitive work possessing “a directness, a unity, and a power which one does not always find in the work of standard masters.”36 Along with collector Abby Aldrich Rockefeller and dealer Edith Halpert, who would later represent Pippin in New York, Cahill was seminal in fostering a deepening appreciation of the aesthetic merits of American folk art. The obvious connection between the appreciation of Americana and an enthusiasm for the work of Horace Pippin is also evident in Juliana Force, who as the director of the Whitney Studio Club and an “avid early-collector of folk art,”37 acquired for the Whitney its first example of contemporary self-taught art—Pippin’s Buffalo Hunt, purchased from his second one-man show at the Robert Carlen Gallery in 1941.

The inclusion of four of Pippin’s canvases in MoMA’s “Masters of Popular Painting,” and his subsequent participation in the Museum’s national touring exhibition of the same name—which traveled to Northampton, Massachusetts; Louisville, Kentucky; Cleveland, Ohio; Kansas City, Missouri; and Los Angeles, California—exposed the artist to a broad new audience. Pippin kept in touch with Christian Brinton, to whom he wrote on July 10,1938, with details of MoMA’s painting selections. There was a warm and homey aspect to Pippin’s dealings with this foppish and sophisticated expert on Oriental and Russian art, whose portrait he would paint in 1940. The artist concluded his letter by saying: “My wife would like to know the date of your birthday so she can bake the cake.”38 While many in the area continued to champion Pippin’s work, others, namely “Chester County artists of the conservative school,” saw the untrained artist’s successes as evidence of “a ‘leftist’ movement that has sprung up in their midst.”39 In 1938, Mrs. W. Plunket Stewart, the socially prominent wife of a well-known Chester County sportsman, paid nearly $100 for Pippin’s painting The Admirer (1937), which she purchased from a local show sponsored by the art association and the West Chester Garden Club. A contemporary news account recorded that the transaction roused the ire of the conventionally trained exhibitors whose work did not sell. The following year Mrs. Stewart had her portrait painted by Pippin,4° and The Admirer entered the collection of her brother, W . Averell Harriman.

In the spring of 1939, Chester County resident and Pennsylvania Academy-trained artist Elizabeth Sparhawk-Jones41 (1885-1968) contacted her friend Hudson Walker to alert him about Pippin’s work. Walker, who then had a gallery in New York on 52nd Street, wrote to Sparhawk-Jones on April 13, 1939, to express his thanks for looking up Pippin: “Three Pippins arrived yesterday, and after only a cursory look, I am very enthusiastic about them.”42 Although he could not guarantee to schedule a show any time soon, he promised to let her know if he had any luck selling the work. In Walker’s letter to Pippin two days later. he ended by saying, “I appreciate Miss Sparhawk-Jones’ letting me know of your work, and I hope I can do something with your paintings.” Sparhawk-Jones would remain an active advocate on Pippin’s behalf. In 1942 she wrote the director of the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts urging him to invite Pippin to exhibit at the Academy’s prestigious Annual: “For me he is one of the few real artists in our century, when he is at his best.”43 Although there is no record that Walker ever sold any of Pippin’s works, he was nonetheless catalytic in Pippin s career. In 1939, Christian Brinton brought Philadelphia art dealer Robert Carlen (1906—1990) to New York to show him Pippin’s work at Walker’s. In December 1939, Carlen became Pippin’s primary dealer.

At this stage in Pippin’s life, it is interesting to note the similar trajectory of his career to that of Anna Mary Robertson Moses, called Grandma Moses, who along with Pippin rose to great prominence in the 1940s. A New York state resident who was twenty-eight years older than Pippin, Moses started painting late in life, as do most self-taught artists.44 At first she showed her work at county fairs, and in 1938 she had several works in the women’s exchange housed in a local drugstore in the town of Hoosick Falls. By chance they were seen by collector Louis Caldor, who brought examples to the New York art dealer Otto Kallir. In 1940 Kallir gave Moses her first exhibition at Galerie St. Etienne which was modestly titled “What a Farmwife Painted.” By the time collector and writer Sidney Janis included both Pippin and Moses in his 1942 publication They Taught Themselves, Moses was not vet as well known as Pippin, who by then had had major exhibitions in Philadelphia, New York, Chicago, and San Francisco. Although Pippin too, painted “memory pictures” of his childhood, such as The Milkman of Goshen (1945), and the rustic charmer Maple Sugar Season (1941), it was the older woman’s more idealized and sentimental vignettes of earlier, simpler times that would capture public fancy in a nation facing grim wartime realities. By the mid-forties, Grandma Moses’s images, derived in part from magazine illustrations and greeting cards, were themselves made into greeting cards that were immensely popular. Although Pippin’s work would be reproduced in such mass-circulation publications as Newsweek (1940), Time (1940, 1943), Life (1943, 1946), Vogue (1944), and Charm (1944), and his still-life painting Victory Vase (1942) was selected for a nationally distributed holiday greeting card, he never achieved Moses’s broad popular following. By contrast, Pippin’s bolder compositions and color schemes and more emotionally complex and thematically sophisticated paintings would be championed by aficionados of Philadelphia’s Main Line and in New York and Hollywood, where a group of politically progressive writers, actors, and producers were familiar with his work. Such personalities as John Garfield, Ruth Gordon, Sam Jaffe, Charles Laughton, Albert Lewin, Philip Loeb, Clifford Odets, Claude Rains, and Edward G. Robinson owned Pippin’s work in the forties. According to the Daily Local News February 23,1943, Harpo Marx “negotiate[d] for the purchase of a Pippin,” although there is no evidence that he actually bought one.45

Of the succession of men and women who believed in Pippin’s art and facilitated his career, by far the most instrumental was Robert Carlen, who opened a gallery on the ground floor of his center city Philadelphia home in 1937. In the late twenties he had studied painting at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, and he liked to recall having been there at the same time as Ralston Crawford and Robert Gwathmey.46 He married former Alice Serber in 1935. With catholic taste and an adventurous yet discerning eye the ebullient Carlen showed a variety of American art and folk art as well as such contemporary Europeans as Kathe Köllwitz, whose work came to him via Hudson Walker. Carlen easily communicated his infectious enthusiasms to those around him, and many of his early clients were his own family and friends. The Carlens lived directly across the street from the Leof-Blitzstein family, to whom his wife was related by marriage. The Russian-born Dr. Morris Leof and his suffragist partner, Jennie Chalfin, formed the heart of Philadelphia’s free-thinking Jewish intelligentsia.47 The talented circle of friends and relatives at their soirees included playwright Clifford Odets and musician and composer Marc Blitzstem. Mrs. Carlen’s sister-in-law Madelin Blitzstein published an early article on Pippin in 1941, and Dr. Leof purchased Pippin’s Country Doctor (1935). Odets, who regarded Dr. Leof as a surrogate father, would later own several Pippins, including Country Doctor.48

The business and personal relationship forged in 1939 between Horace Pippin and his dealer Robert Carlen proved an enduring bond. Carlen immediately arranged an exhibition for Pippin in his gallery, scheduled for January 1940, and introduced Pippin to the collector Dr. Albert C. Barnes, who would write the accompanying essay. Barnes, who had amassed an extraordinary art collection, was a complex, quarrelsome, self-made millionaire49 who since 1923 had been waging a personal war against the art establishment. In that year he had suffered public rebuke by Philadelphia’s conservative art critics, who reacted with alarm when part of his avant-garde collection of modern and expressionist art was exhibited at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts.50 From then on he vowed never to admit anyone with official art connections to view his holdings. With few exceptions, the only way to see his paintings was to enroll as a student in the art appreciation classes offered by his foundation, and the admission selection process was capricious. After being introduced to the artist by Carlen, Barnes invited him to tour his art works and to become a student at his foundation.51

Writers on Pippin have long wondered about the effect on Pippin as a result his exposure to Barnes’s collection of Impressionist and Post-Impressionist art. Tradition has it that Pippin was not an attentive student, dropping out after several weeks of snoozing through classes.52Selden Rodman recorded that Pippin reportedly criticized Matisse’s palette by commenting: “That man put the red in the wrong place.”53 Claude Clarke, who himself studied at The Barnes from 1939 to 1944, recalls that Pippin, who, he says, attended classes at the foundation for five or six months, admired Renoir, once commenting with characteristic humor, “That guy Ren-oor, he was pretty good. And he left a little bit for me too.” Looking at Renoir another time, he told Violette de Mazia, Barnes’s associate, “I’m going to take colors out of that man’s painting and get them into mine.”54 According to another much-told anecdote, Barnes once asked the artist whose work he most favored in his collection, and Pippin said it was Renoir because the pictures were full of sunlight and because he enjoyed looking at the way Renoir depicted the nude models.55 To Clarke, Pippin:

was impressed by some of the things that he saw at the foundation but he felt that after he had seen enough he went back to what he was doing …. Sometime Barnes would call [Pippin] to give him a suggestion and then Pippin would say to Barnes, “Do I tell you how to run your foundation? Don’t tell me how to paint.”

Although as a young man Pippin had worked crating oil paintings, it is likely that he first saw modernist abstractions in 1938, when he showed his work at MoMA. His subsequent experience at The Barnes likewise exposed him to modernism. Yet he never expressed interest in abstraction or expressionism. As with many self-taught painters, Pippin believed he never invented forms or colors and regarded himself as a realist.’6 In a conversation between Pippin and art patron Roberta Townsend, who visited his studio while he was working on one of his Holy Mountain series (1944-1946), the artist called her attention to the sky in the painting, saying: “Now those young artists [referring to students at The Barnes Foundation worry about the sky. They argue about how it should be. It never worries me. I just paint it like it is.”57 In a similar anecdote recounted by the painter Edward Loper, who recalled going out to West Chester to visit Pippin when he was working on West Chester, Pennsylvania (1942), Pippin said:

“Ed, you know why I’m great?” I said “No,” because I really wanted to know. I said “No. Why?” He says, “Because I paint things exactly the way they are. … I don’t do what these white guys do. I don’t go around here making up a whole lot of stuff. I paint it exactly the way it is and exactly the way I see it.”58

Albert Barnes bought at least one painting from Pippin’s first show at Carlen’s, his associate Violette de Mazia bought another, and on his advice, the actor Charles Laughton purchased one as well.59 Barnes was an irascible and complicated man whose support for Pippin was just one facet of his lifelong interest in African-American culture. Predisposed in favor of Pippin, Barnes had a deep appreciation for self-taught artists: works by the American John Kane and the Europeans Jean Hugo and the Douanier Henri Rousseau were in his collection. That Pippin’s professional career was at its start, that his prices were low, and that he was an artist whose cause could be championed to great effect, were all factors that likely appealed to the collector.

Barnes manifested his deep admiration for African-American music in a variety of ways. For example, he sponsored trips to the South to collect and record black folk music.60 He also hosted an annual choral concert of spirituals to which invitations were highly prized. At his January 1940 soiree, his guest, the photographer Carl Van Vechten, first apprised the collector that James A. Bland (1854-1911), composer of “Carry Me Back to Old Virginny,” “In the Evening by the Moonlight,” and “Dem Golden Slippers,” was in fact an African American. When Van Vechten later informed him that Bland was buried in an unmarked grave in Merion, Barnes’s own township, Barnes resolved to have the remains transferred to a small park and to erect a monument there. He wrote to Van Vechten on February 20, 1940: “We must have a Negro sculptor,” expressing his intention of asking Horace Pippin, then a student at the Foundation, if he had ever done modeling.

When Barnes subsequently wrote the photographer that an unnamed sculptor had been obtained for the proposed monument, presumably it wasn’t Horace Pippin. With the exception of the whittled, low-relief war materiale with which he had decorated the frame of his celebrated The End of the War: Starting Home, Pippin worked only on canvases and burnt-wood panels. The project soon stalled when Barnes withdrew his efforts due to personality conflicts and the failure to obtain permission from Eland’s relations to move his remains.61

Van Vechten, who was working on a photographic series on African-American cultural figures, was likely introduced to Pippin by Barnes. He photographed the artist at the foundation. As with many of the collector’s associations, the friendship between Barnes and the photographer eventually cooled. In a 1954 letter to a friend, Van Vechten summed up his relationship to Barnes and his collection:

Matisse once said to me that it was impossible to see French pictures of the periods represented without visiting this Collection. “Nowhere in France,” he went on, “can anything like it be seen.” I have visited the collection at least 8 times (perhaps more). At one time, indeed, I was the Doctor’s “white-headed boy,” due to our mutual interest in Negroes.62

In his dealings with gallery owner Robert Carlen, Barnes was no less mercurial. In Alice Carlen’s description, the two “were both characters and understood each other as characters.”63 In addition to the work of Horace Pippin, the collector and the dealer shared other aesthetic interests, such as Pennsylvania-German furniture and folk art. Their intricate relationship is revealed in their varied correspondence between 1941 and 1943. Carlen’s exceedingly polite manner and deferential attitude is evident in his letter of February 16, 1941, regarding Pippin’s painting Fishing in the Brandywine (1932):

The reason for bringing it out [to the foundation] is that Horace is very anxious for me to place these canvases, and knowing that you were especially interested in the picture to allow you to have the right to purchase it at whatever price you may care to pay.64

The next day Barnes responded to Carlen in an ambiguous tone: “I couldn’t find room for his Fishing in the Brandywine and suggested to four people that they buy it, but all said they had no money to spare.”

When, in June 1941, Barnes was instrumental in arranging an exhibition for Pippin at the San Francisco Museum of Art (later renamed the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art), the collector wrote the dealer that he “would not want anything but first-class examples to be shown” and indicated that he would “be very glad to help select the ones to be shown.” Carlen wrote him the following day to say, with extreme courtesy, that “Any new [paintings] that Horace produces over the next few months will be submitted to you for the decision to show or not.” Earlier, Carlen had likewise deferred to the collector by inviting him to participate in making selections for Horace Pippin’s Guggenheim Fellowship application, “Do you think you would find a chance to help me make the selection of the paintings to be submitted?”

Carlen often wrote to share news of Pippin’s career and to periodically offer Barnes goods for sale. On January 2, 1942, he let the collector know that he had sold two more Pippins, and then he itemized other art items available for sale, such as santos and retablos. The copy of this letter in the Barnes Foundation archives is marked with a penciled “no ans,” indicating Barnes’s impolite decision not to respond. In Carlen’s penultimate letter to Barnes, written on May 25,1943, the dealer first tried to interest him in a rare book on Pennsylvania-German pottery and then went on to note, “I just saw an exhibition of paintings by a young Negro artist Jacob Lawrence at the Downtown Galleries, N. Y. C. I thought you might [enjoy?] knowing about the show as I found it a very fine one.” There is no indication that Barnes ever followed up on Carlen’s lead.

According to Mrs. Carlen, the two became estranged because Barnes wanted to continue to buy Pippins at the prices quoted at the time of Pippin’s first exhibition. Barnes was “irritated and angry” when Carlen, as a good dealer, raised the prices as the market for Pippin’s work increased. In addition, he wanted to have the right of first refusal on all of the artist’s work. Although he complied initially, Carlen soon realized he could not honor this arrangement because he needed to expand the market for Pippin by first offering the paintings to others. Barnes resented being preempted, and his dealings with Carlen soured. He subsequently criticized Carlen for exploiting his artist when the dealer secured a commission from Vogue in 1944.65 In June 1946 a testy Barnes wrote Carlen to complain of the account of Pippin’s discovery published in the current issue of the NAACP publication The Crisis, an inaccurate account in Barnes’s mind, that minimized his own contribution because Carlen purportedly misinformed the reporter.66 A few months later, following Pippin’s death, Robert Carlen took the writer Selden Rodman to visit Barnes in preparation for his monograph on Pippin. The author was allowed into the foundation, but the dealer was told to “wait outside.”67

Pippin’s first exhibition at Robert Carlen’s gallery, of twenty-two paintings and five burnt-wood panels, ran from January 19 through February 18,1940. It was a triumph for both dealer and artist. The show was well reviewed, and a short feature on Pippin appeared in Time magazine on January 29.68 A few days after the exhibition closed, Carlen wrote Hudson Walker: “The Pippin show has been a very fine boost for me and seems destined to carry on stronger. “69 A reporter for West Chester’s Daily Local News asked Horace Pippin for his reactions a week after the exhibition opened:

It sure was a surprise to me the way people like my pictures. They’re responding better than I ever thought they would. The way things look now it will be a sell-out, and I won’t have any pictures to bring back after the show’s over. Yes, sir, the boys are doing me good. . . . I’ve been running back and forth to Philadelphia so much I haven’t had much time to do any work in the past two weeks. I’ve got to get busy and get enough pictures together for another show, maybe in New York. I believe the people there will like ’em too, same as they do in Philadelphia.7°

Looking back at his career from a vantage point six years later, Pippin told an interviewer for The Crisis: “[That show at Carlen’s] was my most successful show. After I’d been there, New York wanted me and Chicago wanted me, and all the rest of them wanted me.”71

Robert Carlen served as the epicenter of a seism of interest in Horace Pippin’s art. The artist’s New York show was being planned even before the one in Philadelphia closed. It is useful to recollect that in 1940 the most prestigious galleries in New York did not show contemporary American art. For example, it would be two years before Peggy Guggenheim opened her gallery Art of This Century, providing an early springboard for Jackson Pollock.72 When New York’s Bignou Gallery decided to mount an exhibition of Pippin’s work, it was the first time they had chosen to represent an American artist. Ever attentive to Pippin’s activities, West Chester’s Daily Local News proudly covered the October 1940 opening of the New York exhibition:

It’s a far cry from East Miner Street [the location of the West Chester Community Center] to East 5yth street, and Horace Pippin has the honor to be the first American, regardless of race, to be represented by a one-man show in the exclusive New York gallery where, heretofore, only the work of such foreign masters as Renoir and Matisse was shown.73

When interviewed in his home in West Chester, Horace Pippin told the local reporter: “I was there when the pictures were hung and the exhibition was opened, and I never saw so many reporters. Everybody treated me swell—especially the press.” When asked to compare the Philadelphia and New York exhibitions, Pippin said: “I’ve got a better assortment of paintings in this show and I look for some of them to go over big.” Although his dealers did not sell as many works in New York as had been sold in Philadelphia, this well-reviewed show, in turn, opened new doors for the artist. Pippin’s attitude to his subsequent fame remained philosophical. When in 1946 he was asked about his successes, he said: “Now why do I want to get up so high? Leave that to somebody else. If I don’t go high, when I fall, if I do, I won’t have far to go.”74

Robert Carlen liked to recount that on their way home from the Bignou opening Pippin saw a particularly memorable configuration of clouds and twilight color in a stretch of the Pulaski Skyway in New Jersey that the artist would later incorporate in the background sky of Christ and the Woman of Samaria (1940).75 As a dealer, Robert Carlen was a masterful manager of Pippin’s career. On January 26,1940, just eight days after the close of Pippin’s debut exhibition in his gallery, Carlen wrote to the Guggenheim Foundation to inquire if it were not too late for Pippin to apply for 1940. He referred to Pippin as an artist “whose work is as complete an expression of native American art as any ever created,” who painted “strong emotional interpretations of American landscapes and American life.” Prematurely, he volunteered a list of eight names of Pippin’s supporters including Marc Blitzstein, Charles Laughton, and artist Waldo Pierce.76 Indeed, the deadline had passed and he had to wait to apply until the fall.

A formal application was submitted in October 1940. Pippin’s brief but trenchant application statement, undoubtedly drafted with Carlen’s assistance, spoke of his interest in the Southern landscape and in recording the lives of African Americans:

It is my desire to go down South, to Georgia, Alabama, North and South Carolina, to paint landscapes and the life of the Negro people, at work and at play, and all other things that happen in their everyday living.77

Pippin, whose wife was from North Carolina, had on at least one occasion traveled south in the twenties. His burnt-wood panel Autumn, Durham, North Carolina (1932) is a later record of that visit. To support Pippin’s application, Carlen offered the names of six references: Holger Cahill, director of the WPA Art Program; Alain Locke, professor of philosophy, Howard University; Albert Barnes; Max Weber, painter; Dorothy C. Miller, assistant curator of Painting and Sculpture, MoMA; and Julius Bloch, painter. On February 4, 1941, well after the October deadline, an irrepressible Carlen wrote the director of the Guggenheim with news that he felt would lend support to Pippin’s application, namely that the Barnes Foundation had purchased another painting and that Pippin’s End of the War had been acquired for the permanent collection of the Philadelphia Museum oif Art. Here and in other contexts, Carlen adroitly obfuscated the fact that he himself had donated the painting to the Museum, where it was accessioned on January 28 1941.78

The fall of 1940 was a propitious time for Pippin, who had passed beyond the initial support of his West Chester community and was moving full tilt into the mainstream art world. The best of his references spoke of his originality and the promise of future success. Barnes commented: “His capacity for growth is revealed in his recent work and I believe that, given the opportunity, he will become one of the most important painters of our age.” Philadelphia artist Julius Bloch, who also knew Pippin personally, wrote: “Pippin is entirely original and I believe his future work will be a worthwhile contribution to the art and culture of his time.” But Miller and Cahill were noncommittal. Although Cahill wrote that Pippin’s project to travel south “promises very well indeed” because of “the interesting personal character” and the “deeply racial quality” of Pippin’s work, Cahill nonetheless chose to rank Pippin sixth of the six references he wrote for the Guggenheim that year.79

Alain Locke, who that year wrote Guggenheim recommendations for three African-American artists—Wilmer Jennings, Hale Woodruff, and Horace Pippin, was equivocal:

Frankly I am puzzled for an opinion! Pippin is a very original and in some canvases a startlingly original painter. What would come from him in terms of a Southern trip and exposure for the first time to the South and the Negro in that locale is only to be guessed at; the result might range anywhere from something stupendously new to an outright fizzle. It is a gamble, but probably a very worthwhile gamble!80

Of the fourteen hundred applicants for fellowships in 1941, only sixty-three were named new fellows and fifteen others had their fellowships renewed. The advisory-committee for applications from artists—Gifford Beal, Charles Burchfield, James Earle Fraser, Boardman Robinson, and Mahonri Young—recommended seven painters and sculptors and two photographers, including African-American sculptor Richmond Barthé. But Pippin was not among them. It may well be that Max Weber’s letter complaining that his name had been given to the committee without his knowledge or consent, proved the decisive factor.81 Horace Pippin never again applied for a Guggenheim award. Nor did he realize his proposed plan to travel south on a painting trip. Yet he would create many memorable images of the southern landscape and of black folk at work and at play.

Robert Carlen mounted his second one-man show of Pippin’s work, from March 21 through April 20,1941. It included thirteen canvases and eight burnt-wood panels. Giving him a mere ten days lead time, Carlen wrote to Albert Barnes on March 11, 1941, to ask him to write an essay for the catalogue of Pippin’s forthcoming show: “As I would like to send out a catalogue to a number of collectors and museums on this show, I feel it would greatly add to the interest in this show if you would write something about Pippin’s new work.” Three days later Barnes responded in the affirmative and noted that he could not “find time to go to your place so the only thing to do is for you to send a number of his latest paintings to our gallery sometime tomorrow, Saturday.” He planned on “think[ing] over the content of my article either Saturday afternoon or Sunday morning,” and invited Carlen to collect the paintings on Monday morning.

In his finished essay Barnes asked rhetorically what might explain the changes in Pippin’s work since his first show the year before. Obliquely valorizing his own role in the artist’s life, Barnes noted that “only one explanation of the change seems possible: Pippin has moved from his earlier limited world into a richer environment filled with the ideas and feelings of great painters of the past and present.”82 Working both sides, Carlen sent Barnes’s essay to museums, and when these institutions showed support, he wrote immediately to Barnes. Nine days after Pippin’s show opened, he sent a postcard to Barnes alerting him that the Whitney Museum had just bought a Pippin, observing, “The exhibition has been drawing quite a large attendance every day and I hear it has been causing quite a bit of discussion.”83

Pippin’s next major exhibition fell in place when Alice Roullier, secretary of the Arts Club of Chicago, wrote a letter of inquiry to the Bignou Gallery. In his reply of February 11,1941, Bignou director George Ketter said, “I am glad to learn that you are interested in this man’s work, as I think he is one of the good painters in the country at this time.” Pippin’s works were to be shown with those of Salvador Dali and Fernand Leger from May 24 to June 14, 1941. An industrious publicist, Carlen wrote to Roullier in mid-March offering to lend photos, a copy of MoMA’s Masters of Popular Painting catalogue, and a book of clippings. Ever mindful of the potential for press coverage, he went on to remark: “There is a fine human interest story that can be turned over to the Chicago newspapers which I am sure will prove of great interest to them especially as Chicago has so huge a Negro population and surely will be [of] interest to those readers!”84

Carlen sent out an announcement of the upcoming Chicago show that was quoted in the March 26, 1941, West Chester Daily Local News: “To be invited to exhibit there is one of the most important honors tendered to any living painter. . . . Pippin is without question on his way to being nationally recognized as one of the most original painters ever discovered.” Midway through the run of his own Pippin show, he wrote again to Alice Roullier to bring her up to date about Pippin:

I thought you would find it extremely interesting to know that this show of Pippin’s recent paintings has been one of the most talked of shows for years. We have had a tremendous and greatly impressed attendance. I am certain you too will experience the same sort of reception both of his shows have had in the East. He is undoubtedly one of the most interesting and original American painters ever discovered, and when you see this work you will readily understand why when this work is shown it has such drawing power and stimulates a great deal of discussion.”85[emphasis added]

A month later Carlen again wrote Alice Roullier asking her to send catalogues to Lessing Rosenwald, Mr. and Mrs. John Rockefeller, Jr., Mr. Hubachek of Chicago, and the curator of prints at the Art Institute. He also suggested she send catalogues to:

many of the museums situated in the middle west and western part of the U.S., as I know the curators of painting in many of the museums have heard of Pippin and are interested in seeing his work, and they would make a point of coming to see the show if they know it was being held in Chicago. The assistant curator at the Art Institute was in my gallery a few months back and I showed him several of Pippin’s paintings I had here at that time. He was greatly-impressed and made a note to keep this work in mind.86

Ever the booster, Carlen then described some of the recent publicity about Pippin and noted in a postscript that he had sold fourteen paintings out of the April show, that Barnes had acquired two new ones, and that “the Whitney Museum [acquired] one—a short time before that the Phila. Museum acquired their example. I believe this information will be of good value to your Chicago critics as to how well American art is selling today.” In late May the dealer and the artist traveled to Chicago by train for the exhibition that would feature three artists. Salvador Dalí, who also was having his first show in Chicago, was allocated the Arts Club’s largest gallery. Pippin’s thirty-nine paintings and burnt-wood panels were assigned two smaller rooms, and Fernand Leger’s twenty-five watercolors and drawings were in the hallway. The Chicago press responded with an avalanche of coverage of the event that reflected their fascination with Dali, whose Surrealist antics always made good copy.87 A Chicago Herald-American account of the tea held on the May 24 opening, first dealt with the European exhibitors and then went on to report:

There was a third guest of honor, the quiet, retiring Negro painter Horace Pippin, holding court in his little gallery among his painted lilies and homey snow scenes, but he would be the first to disclaim credit for the box office crowd. The crowd was there to see Dali and his works and they were not disappointed.88

Artist Claude Clark recalls that Alain Locke enjoyed recounting a tale about the meeting of Horace Pippin and Salvador Dalí in Chicago:

Dali was a little taller than Pippin. And Pippin was introduced to him. And the way Locke tells it, that he looked up at this tall guy and Dalí extended his hand and Pippin says to him, “Is you an artist too?” And Locke says that Dalí pulled his hand back and went over in a corner and pouted the rest of the evening. So, but Pippin didn’t know people. And he just did what he was doing.89

Despite Carlen’s anticipation of the potential curiosity on the part of Chicago’s large African-American population for the “fine human interest story” of Pippin and his work, no such interviews materialized in the press. Similarly, the Art Institute of Chicago did not act to purchase any of the artist’s works. Nonetheless, the experience of the Chicago exhibition was worthwhile for Pippin. A few weeks after their return to the East Coast, a voluble Carlen wrote to Albert Barnes to assess their trip:

As you probably know Horace and I went out to Chicago for the opening of his show [at the Arts Club]. We were out there four days and Horace said he had a marvelous time. We spent quite a bit of time at the Art Institute and Horace especially enjoyed the Flemish and Dutch paintings of the 16th and 17th centuries. His favorite was Lucas Cranach, and on the train back to Philadelphia he kept commenting on the marvelous qualities that this master obtained in his canvases. Horace felt that seeing these pictures were alone worth the effort of making so long a trip. It will be interesting to see what effect, if any, these pictures will have on his work from now on.9°

There is no indication that the finely rendered, sensuous forms of the sixteenth-century German artist Lucas Cranach, made an impact on Pippin’s subsequent work. Nonetheless, it is telling that Pippin, who understood himself to paint exactly what he saw, so enjoyed Cranach’s precise style and detailed observations.

Pippin settled back into a productive period of painting. If he had once responded to a query as to why he painted by answering “Out of loneliness,”91 and at another time told a reporter that he did much of his work at night, when he was often low-spirited, when he had what his wife called “blue spells,”92 he was now buoyed by the new audience for his art. In August 1941, when Pippin’s garden would have been at its peak, Robert Carlen wrote to Albert Barnes, “I just received a new Pippin canvas; it is a striking still life of flowers, very colorful.”93 In November Pippin sent a postcard to Carlen to say that he was anxious to bring his new work to his dealer as “I know you will like them, for I know of myself that I have never made any better.” He concluded by requesting payment and announcing that he and his wife were invited to dinner at the home of Miss Fllen Winsor, one of his collectors who then owned Mountain Landscape (c. 1936) and The Getaway (1939).94 In another postcard written on December 15, Pippin confides: “I am on the job. I hope to God that New York is a knock-out.”

The New York to which Pippin referred was the exhibition at Edith Halpert’s Downtown Gallery, entitled “American Negro Art, 19th and 2oth Centuries,” whose December 8 private opening was overshadowed by Pearl Harbor. In 1941 Edith Halpert was introduced to the range and quality of art by African Americans by reading Alain Locke’s recent book, The Negro in Art, which included material on Pippin. Fired by a desire to educate the public about the strong work produced by black artists, she resolved to host a major exhibition in her gallery’s new quarters on 51st Street. She set up the National Negro Art Fund to purchase art for public collections that was to be financed in part by a portion of her commissions. In addition, she proposed that her own and other New York galleries each add one contemporary black artist to their stables. Pearl Harbor and the United States’s entry into World War II eclipsed Halpert’s cultural work.95 As a result of this show, however, she did add Jacob Lawrence and Horace Pippin to her roster of affiliated artists. Pippin’s visibility was greatly enhanced when art critic Robert M. Coates, writing for The New Yorker, reviewed the exhibition and singled him out by commenting that “It’s Pippin . . . who steals the show.”96

Claude Clark recalls that Carlen asked him and his older brother to transport Pippin’s work to New York for the show. Their old Buick, with the Pippin paintings wrapped in a blanket in the back seat, was stopped by the police just outside Philadelphia. Unfortunately, Clark’s brother had forgotten his driver’s license, and so they were led to a police station and fined twenty-five dollars. The police raised the blanket but were uninterested in the pile of paintings underneath. The brothers were obliged to return home to pick up the license and finally arrived in New York only minutes before the exhibition’s scheduled opening. 97 On January 2, 1943, Robert Carlen wrote to Albert Barnes that as a result of the Downtown Gallery’s show, he had sold at least two paintings, The Squirrel Hunter (1940) and Lilies (1941): “The commission on these sales goes to the National Negro Art Fund to be used for the purchase of other Negro artists’ works to be presented to schools and institutions.”98

Pippin’s next exposure to a national audience came in the spring of 1942 when, through the efforts of Albert Barnes, the painter was given a solo show at the San Francisco Museum of Art. Douglas MacAgy, the assistant curator, had been a student at the Barnes Foundation. In June 1941 the collector wrote to Robert Carlen to say that he had been asked informally by MacAgy if it were possible for his museum to host an exhibition of Horace Pippin’s works. Barnes expressed the hope that Carlen would follow through on this inquiry and “give it preference to all other possible places of exhibition because three of the best students we ever had are located in San Francisco, teaching at the University of California and forming practically the working basis of the Museum.”99 Carlen accepted with alacrity and arrangements were in progress by that fall. In a letter on September 3, Carlen alerted Barnes of the forthcoming publication of Sidney Janis’s book on self-taught artists. which contained a section on Pippin, and he added, “I am deeply grateful for vour kind cooperation and aid in making this San Francisco show a possibility.”100 Carlen kept Barnes informed, writing him in March that he was “sending almost all of the canvases Pippin produced [in] the last three years, and there is no doubt the assembly of all of these canvases in one exhibition will be tremendously impressive.”101 Nine days later the dealer again contacted Barnes to say, “I have been writing to a number of important people living out in California asking them to do whatever they can to arouse interest in the [forthcoming] Pippin exhibition”102 One of recipients of Carlen’s entreaties was the poet Langston Hughes, who belatedly wrote the dealer from Yaddo seven months later to thank him for his letters concerning Pippin’s San Francisco exhibition: “Unfortunately, I was in Chicago at the time, and so could not see the show, but I advised several of my friends in the West of it. I have had the pleasure of seeing a few Pippin paintings and found them most interesting.”103

Carlen worked with San Francisco director Grace McCann Morley on organizing the exhibition. She had been instrumental in bringing MacAgy and his wife, Jermayne, west to San Francisco in 1941. That Morley gave Arshile Gorky an important, early show the year prior to Pippin’s exhibition, is an indication of her pioneering support of the new abstract painting in both New York and San Francisco.1°4 Following her winter 1942 trip east in which she missed getting to Philadelphia, Morley wrote Carlen:

I stopped in at Mrs. Halpert’s [in New York] to see whatever examples she might have of the work, especially recent, of Pippin. She has two charming flower pieces with which I was much impressed. I like this later phase of his work very much more than earlier works which have always seemed to me somewhat lacking in color.

On April 14, the opening day of the exhibition, Morley wrote Carlen: “You would be pleased with the show I think; it looks very handsome. Pippin certainly had beautiful color. [The show] occupies a very prominent, though fairly small, gallery as galleries run. It is just as well, for his things are on the small scale.” Two weeks later she wrote again to say, “The Pippin show grows on one on greater acquaintance, and I am more impressed by the fine quality of his color and the freshness and directness of his vision.”105

Pippin’s exhibition at the San Francisco Museum of Art was his sole 1942 show. The pace of public exposure quickened in 1943, during which time his paintings were exhibited in three distinct contexts: nationally prestigious surveys of contemporary fine art, a retrospective of American self-taught painters, and surveys of work by African-American artists. Not only was Pippin invited to show at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts’s annual exhibition, but his painting John Brown Going to His Hanging (1942) was awarded an Academy purchase prize of six hundred dollars. It was unprecedented for an unschooled artist to win an award at the nation’s oldest art museum and art school, then holding its 138th annual painting and sculpture exhibition. On February 1, Robert Carlen wrote Albert Barnes a newsy letter regarding Pippin and the activities of the Carlen Gallery:

It also looks as though the large John Brown painting I showed you sometime ago is going to be purchased by a museum. If the purchase goes through the announcement of same is going to cause a large amount of comment when the name of the museum purchasing it is known.106

The Academy soon lent John Brown to the Corcoran Gallery of Art in March, when Pippin participated in that institution’s eighteenth biennial of contemporary American oil paintings, another indication of his growing importance. In addition to the shows in Philadelphia and Washington, the Art Institute of Chicago included the artist in their fifty-fourth annual exhibition of American painting and sculpture. In an entirely different framework, Pippin made a return appearance at the Arts Club of Chicago when Sidney Janis included two of his paintings in a survey he curated entitled “American Primitive Painting of Four Centuries,” marking the recent publication of his book They Taught Themselves: American Primitive Painters of the 20th Century.

Yet another forum for Pippin’s work was the newly popular surveys of work by black artists. Both Alain Locke’s 1940 book, The Negro in Art: A Pictorial Record of the Negro Artist and of the Negro Theme in Art, and James A. Porter’s Modem Negro Art, published in 1943, stimulated interest in the accomplishments of black visual artists. In early January 1943, Boston’s Institute of Modern Art (then affiliated with MoMA and known today as the Institute of Contemporary Art) organized with Smith College Museum of Art a traveling show, “Paintings, Sculpture by American Negro Artists,” which included three of Pippin’s paintings. In Philadelphia that year, Pippin was represented in two separate group shows of African-American art. One was at the Pyramid Club, an organization of black artists, which included two of Pippin’s paintings in their third annual exhibition. Pippin showed five works in Robert Carlen’s show “Oils, Water Colors, Prints and Sculptures by Negro Artists of Philadelphia and Vicinity.”

The artist put great value on his participation in the Pyramid Club show, in large part because of the potential for a sale to Barnes, who was scheduled to give an address titled “Art of Negro Africa and Modern Negro America” at the opening ceremonies. Pippin wrote to Carlen on February 1, nearly three weeks prior to the opening: “I wish that the picture I just made will be in this show, that is if you see fit to send in one. The picture is the Domino Game [1943] so that Dr. Albert Barnes can see it. He is the main speaker at the show.”107 Although the doctor may have seen the painting at the opening, he did not purchase it. Days after the exhibition closed, Carlen wrote Barnes that “the Pippin painting The Domino Players is back from the Pyramid Club show, and I have several other small new canvases here I would like to show you.” Barnes did not respond and Carlen included Domino Players in his April show of Negro art. Edith Halpert exhibited it in October and by December had sold it to the Phillips Collection in Washington, D.C.108

Although relations between the dealer and the mercurial collector were beginning to strain, Carlen continued to correspond with him. On March 31, a day before his exhibition was to open, the exasperated dealer solicited the collector’s advice:

I have been trying to get some publicity on my Negro show . . . |and] I have gotten no co-operation whatsoever. I telephoned all the Negro newspapers having offices in Philadelphia several days ago and spoke to the editors in charge and although they professed to be interested I have seen no signs whatsoever from them to date. . . . [I| feel that it would be a great shame if this show were not to be more publicized than it promises to be as I know there are many persons who would be interested in seeing it and who would be greatly impressed by the character and quality of the creative work of our local Negro artists.109

The copy of this letter today in the Barnes Foundation archives is marked in pencil “no reply.” Happily for Carlen and his artists, the Philadelphia Inquirer published an illustrated article on the show shortly after it opened, drawing attention to the work of the twenty-four exhibitors, including Pippin, Claude Clark, Allan Freelon, Paul Keene, Jr., Edward Loper, Raymond Steth, and Laura Wheeler Waring.110 There is no indication that Barnes ever came into the city to see the exhibition. The day before it closed, Carlen wrote Barnes that he had sold two more of Pippin’s paintings out of the show and commented:

This show had a very good attendance and seems to have caused quite a stir in this city from reports I have heard from people who came in to see it. It was gratifying to see this response which clearly showed a great interest especially among the Negroes of the city.111

During the 1940s, Pippin’s relationship to Philadelphia’s active community of black artists was complex. Claude Clark recounts the story of how he and his wife first encountered the West Chester resident. After seeing Pippin’s work at Carlen’s gallery, the Clarks decided that they wanted to meet the artist in person. They took the train to West Chester and after asking several people, were directed to his house. “Pippin opened the door and looked out at us, in a very quizzical way, very curious, and he seemed puzzled.” Clark notes that he introduced himself and said that he was an artist and had come to meet him. Pippin was surprised, Clark recalls, because at that time there was a group of black artists in Philadelphia who were vocal in their hostility for the self-taught artist. Clark recalls that a black artist, well-known in Philadelphia, who “had rounded up a group of other black artists,” had approached Clark to join them in their condemnation of Pippin:

He wanted me to join them to attack Pippin, because [Pippin] was making, earning money. And they said “We went to the Academy, and we … have studied. He didn’t study the same way we did, and he shouldn’t be earning money when we’re not earning money.” So when I talked to Pippin, he said “I don’t understand why they want to fight me.” And I couldn’t explain it either so I went in and we had a nice talk, and from that time on we were friendly.112

Friction between African-American artists who did and did not receive recognition existed within the arts communities in other locations, and did not always pit the trained against the un-trained. Jacob Lawrence recalls that, “we had a similar situation in New York. Some [black] artists were getting recognition; others were not. And it was exactly the same thing. These artists were attacked.”113

Given the condescending, racist comments made by critics in the context of praising the self-taught painter, little wonder that some academically trained black artists resented Pippin’s successes. For example, a March 1941 review of his second show at Carlen’s gallery noted that “Horace Pippin . . . can claim the purchase record for Negro painters in America,” and concluded:

Pippin’s work differs from that of the average American Negro painter trained in the schools. It is not a pale imitation of the white man’s art. In choice of pigments and in courage of contrasts it smacks of racial origin; for, unhampered by theories of technique, he paints with no holds barred.114

Such critical sentiments that measured and valued African-American artists by their distance from “white man’s art,” were commonplace in the forties. The young Romare Bearden ridiculed this attitude in a 1946 article entitled “The Negro Artist’s Dilemma,” in which he identified it as one of the concepts of critical opinion “that constantly reappear[s]” in relation to Negro artists. He derided one critic who reviewed a group show of Negro artists by commenting: “We can say this of it: the farther removed the Negro is from copying the white man’s style or subject matter, the better he is.” Bearden responded by pointing out that, “however disinherited, the Negro is part of the amalgam of American life, and his aims and aspirations are in common with the rest of the American people. 115

An invidious instance of inappropriate comparisons used to praise Pippin’s achievements can be found in a 1944 Baltimore Afro-American interview with Barnes. Measuring Pippin against the well-known, formally trained black painter Henry Ossawa Tanner, the collector exclaimed:

Henry O. Tanner is a pigmy and Horace Pippin is a giant. What Tanner had to say was simply a feeble echo of what had been said by great artists several centuries ago. Tanner’s work is an attenuated and diluted expression of the white man. What Pippin has to say has never been said before. Pippin carries on the work of the great artists, but he expresses himself in his own language.116

While it would be expected that Barnes’s modernist taste would favor the self-taught over the academic, it was exceedingly cruel of him to use his cursory knowledge of African tribal characteristics to diminish Tanner in order to praise Pippin. Claude Clark recalls that “There were people who got angry with [Barnes]” for his dismissal of the earlier black artist.117

Perhaps no word proved more malleable in its application to Pippin than did “primitive,” the adjective Dorothy C. Miller at MoMA had used to describe the artist in 1937. For some writers, it was clearly pejorative. For example, after Pippin’s Cabin in the Cotton III had been awarded fourth honorable mention in the 1944 Carnegie International, a Pittsburgh critic dismissively described the painting as “amusing, as simple as a Mother Goose rhyme and as naive as a Negro spiritual. . . . Whether this particular picture is worthy of the $100 cash award is difficult to decide, as primitives are highly debatable. They are like ripe olives or mangoes— you like them or you don’t.118 Another Pittsburgh writer sought to qualify her use of “primitive” by observing that:

[Pippin’s] paintings are primitive in the best sense, gentle records of war experiences and childhood memories, of which Cabin in the Cotton is a good example. This kind of picture is as much a part of our sentimental heritage as Stephen Foster and “Dixie,” with the field of cotton stretching away in meticulous rows, the log cabin, the washtubs and the sky. Each white puff, each blade of grass is carefully delineated—that’s the way it was in memory, and that’s the way it is!119

It is small wonder that the press release issued by the Downtown Gallery on the occasion of Pippin’s first one-man show there in the winter of ^44, sought to distance the artist from the term: “Originally hailed as a ‘primitive,’ his growing sophistication has gradually eliminated that label.”120

Even Pippin’s most urbane critics struggled with the label. In his 1941 review of the Downtown Gallery exhibition “American Negro Art, 19th and 2oth Centuries,” New Yorker critic Robert M. Coates first commented favorably but briefly on such artists as Romare Bearden, Alice Catlett, and Jacob Lawrence before discussing Pippin, his clear favorite. To Coates, Pippin was “incontestably in the very front rank of modern primitive painters, here or abroad. Indeed . . . Pippin’s skill and resourcefulness have progressed to the point at which it is hardly proper to call him a primitive at all.” Coates concluded by observing:

I suppose, until some more appropriate word can be found, “primitive” will have to be the word we use for a man like Pippin, but I imagine there are not many painters, however “finished” in style they may be, who can fail to admire the dexterity and daring he displays.121

Three years later, on the occasion of Pippin’s first one-man show at the Downtown Gallery, Coates was still expressing his discomfort with terminology:

I don’t know what it is precisely that differentiates the “primitive” artist from what I suppose we must call the sophisticated ones. But if the distinguishing qualities of the primitive are a preoccupation with minor detail and a tendency to play fast and loose with the laws of perspective, then Horace Pippin . . ., is indeed, as he is customarily classified, a primitive. However, in the use of color and the ability to organize and synthesize a scene into a well-balanced composition, he’s about as subtle and sophisticated as the next man, which sort of makes you wonder where sophistication begins and primitivism leaves off.122

An Art News critic who covered Pippin’s 1944 Downtown Gallery show began her review by quoting Albert Barnes’s 1941 comment that Pippin was “the most important Negro painter to appear on the American scene.”123 She went on to observe:

It is interesting to note that the label “primitive” is absent from this analysis which compares the artist’s work with that of Daumier, Cezanne, and Matisse. For like theirs, Pippin’s style is simply the result of an inner vision of burning intensity. Lack of teaching has less do with it than a determination to come as close to that vision as possible.

As Pippin’s national reputation grew, so did his commissions. In May 1943 Robert Carlen wrote to Albert Barnes:

I know you will be delighted to learn that I have just gotten a commission for Pippin to make a painting for one of the most important advertising agencies in this country. It is for the Capehart series and Pippin is free to do whatever he wants in his interpretation of Stephen Foster’s Folk Songs.124