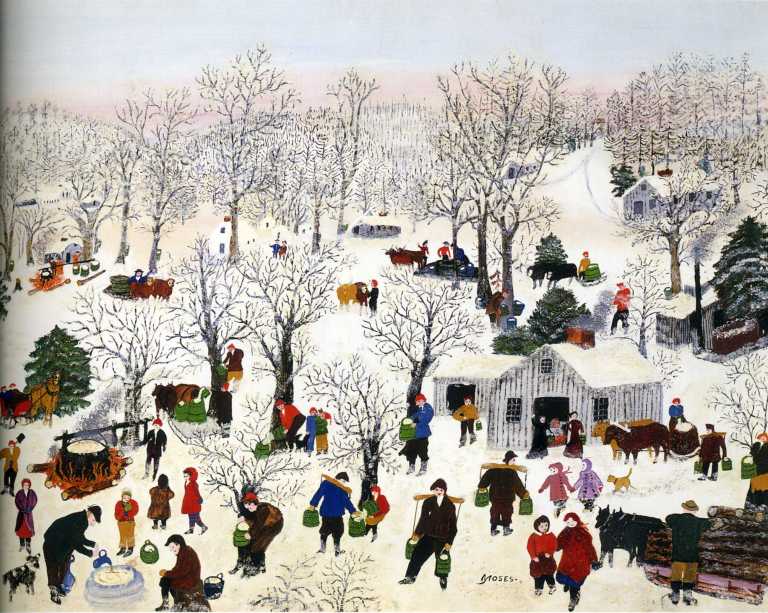

“If asked about lady artists in America,” Cue magazine wrote in 1953, “most Americans would probably mention one, Grandma Moses.”*1Indeed, such was Moses’ phenomenal popularity in the 1950s that her exhibitions broke attendance records all over the world. A cultural icon, the spry, productive octogenarian was continually cited as an inspiration for housewives, widows and retirees. Her images of America’s rural past were transferred to curtains, dresses, cookie jars, and dinnerware, and used to pitch cigarettes, cameras, lipsticks, and instant coffee. Cole Porter, one of her collectors, alluded to the “big dough” pursuing the artist in his lyrics for a 1950 Broadway play.2 She was a drawing attraction at parades and political rallies, courted by presidents and awarded honorary degrees. At the time of her death at age 101 in 1961, it was estimated that Americans had exchanged over IOO million Christmas cards bearing reproductions of her paintings.3

Born a decade past the middle of the nineteenth century, Anna Mary Robertson was raised amidst traditional notions of woman’s domestic duties. Hired out as a maid at age 12, she married farmer Thomas Moses at age 27 and bore 10 children, 5 of whom died in infancy. Her adult life was defined by her multiple duties as a farmwife. For three-quarters of her 101 years, art was a luxurious pastime she could not afford. In 1943 she confessed to an interviewer, “I had always wanted to paint, but I just didn’t have time until I was seventy-six.” Russell Robertson, her farmer father, painted as a hobby, introducing her to grape and berry juice pigments as a young child. She called these girlish efforts “lambscapes.”4

Her father was a strong influence on the young girl in a variety of ways, giving her a sense of her own powerful potential. Moses often told interviewers: “I was along about 9 years old when my father said one morning at the breakfast table, ‘Anna Mary, I had a dream about you last night.’ ‘What did you dream, pa?’ ‘I was in a great, big hall and it was full of people. And you came walking toward me on the shoulders of men.’ As of now, I have often thought of that since.”

Russell Robertson also inspired his daughter in ways he could not have imagined. She confided to a writer who had asked about a candy-pink house in one of her canvases: ‘”Oh, that. Once when I was a little tyke I asked Pa why he couldn’t paint our house pink, and he said houses just didn’t come pink. ‘Well,’ with a little twinkle, ‘that’s a pink house, isn’t it?'”5 To another reporter she related a story that obliquely revealed the power of her father’s approval: “[As a child] I used to like to make brilliant sunsets, and when my father would look at them and say: ‘Oh, not so bad,’ then I felt good. Because I wanted other people to be happy and gay at the things I painted with bright colors.”6

Like most women raised in the nineteenth century, and in much of the twentieth century, Moses was taught that one of woman’s virtues is to please. She seemed to embody the old gender recipe of “sugar and spice and all things nice.” For example, in 1946 she commented: “I like pretty things the best, what’s the use of painting a picture if it isn’t something nice? So I think real hard till I think of something real pretty, and then I paint it.”7 Practical at heart, she returned to painting in her seventies after working with worsted wools for embroidered compositions: “I did not want my pictures to be eaten by moths, so when my sister, who had taken lessons in art, suggested I try working in oils, I thought it was a good idea. I started in and found that it kept me busy and out of mischief.”8

She took pride in her own thrift and ingenuity, painting on things that were left over, in her left-over time. She recalled that in the 1930s, she had made her first painting by pulling together a fragment of thrasher canvas, house paint remains, and an old frame. Her sense of accomplishment in her painting was rooted in her ability to make “something from nothing,” as Lucy Lippard defined the aesthetic of women’s “hobby art” in 1978,9 and was akin to her quilting work, where she transformed cloth scraps into useful and beautiful objects. Curiously, Lippard is silent on the subject of Moses.

Indeed, feminist critics and scholars were uninterested in Anna Mary Robertson Moses when, in the 1970s, they first began reappraising women’s art work, and factoring gender into the analysis of artists’ oeuvres and careers.10 It may be that the artist’s very success counted against her. She was neither forgotten nor neglected, and therefore could not be rediscovered. Society in general tends to desexualize elders, and Moses’ womanly identity took a backseat to her visibility as a visual bard of the American rural experience. Too, within the art world, self-taught artists were much more marginalized than they are now. She was neither part of the canon nor the object of revisionist attention.11

Forty years after her death, it is more than timely to investigate how gender influenced the course of her extraordinarily successful career. The story begins with collector Louis J. Caldor, who happened upon her paintings in a drugstore in upstate New York. He introduced them to the Manhattan dealer Otto Kallir, who soon gave Moses her first solo exhibition. Kallir mounted What a Farm Wife Painted at his recently opened Galerie St. Etienne in October 1940. The matter-of-fact, if infelicitously worded, title communicated both the artist’s rural identity and her status as an unschooled “primitive.” The Herald Tribune reviewer, for example, “went away with the feeling that the most evident thing about the show is the artist’s delight in painting the simplicity of the rural country.”12

In his New York Times review of the show, art critic Howard Devree picked up on the title’s other implication, namely that she was a self-taught painter. He began by noting that “the ‘primitive,’ which has been much to the fore in the early season, crops up again.”13 Commenting on her artworks’ “simple appeal” and “simple decorative effects,” Devree pronounced Mrs. Moses’ exhibit “a very creditable show of its kind.”14 World-Telegram critic Emily Genauer wrote a singularly thoughtful critique, insightfully noting that Mrs. Moses’ “colors are fresh and clear (perhaps because she found expression first through bright embroidery). . . .”15

Genauer did not dwell on Moses’ status as an unschooled artist. Rather she honed in on the visual strength of her paintings. Describing Moses as possessing “an extraordinary natural talent,” she noted that “her textures are rich. Even her drawing is loose and fluid. And her conceptions are at once daring and imaginative.” She was particularly taken with a painting entitled A Fire in the Woods, which she saw as “a challenge to scores of more sophisticated painters. I think especially of a George Grosz canvas in which a similar theme was handled no more excitingly and with no more assurance and success than Mrs. Moses handled it here.”16 These favorable comments by a respected critic would be cited again and again in the succeeding months, in a variety of publications.

Few early writers looked as carefully at Moses’ paintings as had Genauer. In general, the New York press distanced the artist from her creative identity. They commandeered her from the art world, fashioning a rich public image that brimmed with human interest. The Galerie St.Etienne’s debut invitation had referred to the octogenarian artist as “Mrs.,” but it was the New York Herald Tribune that had called her “Grandma.”17Although the artist’s family and friends addressed her as “Mother Moses” and “Grandma Moses” interchangeably, the press preferred the more familiar and endearing form of address. And “Grandma” she became, in nearly all subsequent published references. Only a few publications by-passed the new locution: a New York Times Magazine feature of April 6, 1941; a Harper’s Bazaar article; and the landmark They Taught Themselves: American Primitive Painters of the 20th Century, by the respected dealer and curator Sidney Janis, referred to the artist as “Mother Moses,” a title that conveyed more dignity than the colloquial diminutive “Grandma.”

But “Grandma Moses” had taken hold. The avalanche of press coverage that followed had little to do with the probity of art commentary. Journalists found that the artist’s life made better copy than her art. For example, in a discussion of her debut, an Art Digest reporter gave a charming, if simplified, account of the genesis of Moses’ turn to painting, recounting her desire to give the postman “a nice little Christmas gift.”18Not only would the dear fellow appreciate a painting, concluded Grandma, but “it was easier to make than to bake a cake over a hot stove.” After quoting from Genauer and other favorable reviews in the New York papers, the report concluded with a folksy supposition: “To all of which Grandma Moses perhaps shakes a bewildered head and repeats, ‘Land’s Sakes’.” Flippantly deeming the artist’s achievements a marker of social change, he noted: “When Grandma takes it up then we can be sure that art, like the bobbed head, is here to stay.”

A month after her New York gallery debut, Gimbel’s department store made Moses the focus of its Thanksgiving festival, and invited the artist to speak at its Thanksgiving forum. Although she had seen no reason to attend her October opening at the Galerie St. Etienne, she now agreed to journey to the city for the first time since 1917. Addressing an audience of Long Island, Westchester, Staten Island, and Queens club women who had been assembled at Gimbel’s for a Thanksgiving table-setting contest, she talked about Thanksgiving customs in her childhood.19 “Artist Just by Hobby ‘Doesn’t Mind Fuss’,” declared a headline reporting the event in the New York Times of November 15. The press began to favor a “just us folks” approach to Moses, reveling in examples of her “uncitified” ways.

Besides featuring Moses as a speaker, Gimbel’s mounted an exhibition in its auditorium of fifty of her paintings, store officials capitalized on her identity as a farmwife, and the press followed suit. The New York World-Telegram led off its coverage with the tantalizing observation that “El Greco and Raphael and Van Gogh couldn’t have done it; Picasso and Wood and Dali couldn’t do it. But Grandma Moses did it.”20 It was the simple demonstration of domestic skills. Gimbel’s had supplemented Moses’ art display with “a table beneath the paintings spread [with] samples of Grandma’s culinary talents—home-baked bread, rolls and cake, plus some of the preserves which won her prizes at the county fair.” The public ate it up, so to speak.

When, weeks later, her paintings were shown at the Whyte Gallery in Washington, D.C., one writer would make the same point with words: “She concocted these paintings much as she made her prize-winning jams, with care, with naturalness and using the homely ingredients that she found about her.”21 The press loved to pair and contrast her art and her cooking,22 and the writer Eugenia Sheppard would cleverly conflate these spheres by commending Moses for her “delicious paintings.”23 It is interesting to contemplate this kind of commentary when recalling that in 1950, the young Lee Krasner chose to be engaged in making currant jelly when a New Yorker writer came for a visit at the home she shared with her husband Jackson Pollock.24

Gimbel’s savvy publicists had a field day writing copy for the newspaper advertisements alerting New Yorkers to Moses’ visit. The ad in the New York Herald Tribune on November 14 enthused:

Grandma’s the biggest artistic rave since Currier & Ives hit the country. She’s the white-haired girl of the USA who turned from her strawberry patch to painting the American scene at the wonderful age of8o. You’ll see her. You’ll see the first complete loan exhibition of her wool paintings and American primitive paintings. Come hear what gave her the urge to buy paints and try her brushes on her threshing cloth. Gimbel’s Eleventh Floor. [emphasis added]

Framed as an antiquated “girl next door,” New Yorkers took the all-American Grandma to their hearts.

In the years following Moses’ debut, the popular press often underscored her identity as a simple farmwife. For example, a Harper’s Bazaar feature of 1942 noted: “Daughter and wife, she’s been a farm-woman all her life. She has five children, eleven grandchildren, one great-grandchild; still takes prizes at the county fairs for her jams and pickles; and her cakes stack up with any in Washington county.”25 A year later, a story in a woman’s magazine praised her “farm wife’s adaptability for turning her hand to anything.”26 A contemporary article in The Pathfinder first recounted the accolades of such New York art critics as Genauer and then reminded readers that “she still doesn’t paint until she’s swept the house and done the chores, just as she has been doing for many years.”27 The apotheosis of this characterization may be the Mother’s Day feature in True Confessions (1947) entitled “Just a Mother,” which noted: “Grandma Moses remains prouder of her preserves than of her paintings, and proudest of all of her four children, eleven grandchildren and four great-grandchildren.”28 People adored this simple and ordinary woman whose public presence as “Grandma” had been invented by feature writers.

When Anna Mary Moses spoke at Gimbel’s Thanksgiving forum in mid-November 1940, much of Europe was at war. Against this backdrop of distant conflict, the seasoned copywriters in the store’s publicity department emphasized enduring national values in their ad for the event published in the New York Times (November 14, 1940). They pitched Moses as an old-fashioned American homemaker and only once referred to her status as an artist. Their copy hit more than a note of nostalgia, it struck a whole harmonic chord:

“Over the river and through the woods to Grandmother’s house we go.”We couldn’t go to grandmother’s house so grandmother came to us. Grandmother who ? Grandma Moses, the American girl who made good at 80. You’ll meet Grandma herself today. She’s more than a great American artist. She’s a great American housewife. The sort of American housewife who has kept the tradition of Thanksgiving alive. Fussing with cranberry sauce may seem a bit useless in these turbulent times. It’s not. A woman can’t do much about wars or rumors of wars. She can[sic] fight to make the world a pleasanter place by perfecting her cranberry sauce. As long as American housewives busy themselves with cranberries and chrysanthemums there’ll always be Thanksgiving! [emphasis added]

However traditional her earlier years had been, Anna Mary Moses’ life was more complex than that of a housewife who fussed over cranberry sauce. Nonetheless, she was presented as an authentic embodiment of hearth and home, a dear sweet lady who was not going to bother her pretty little head with thoughts of distant crises. What appealed to Gimbel’s were Grandma’s memory pictures of the holiday, where the only dead creature was the unfortunate turkey.

Thanks to old-fashioned gender politics, Gimbel’s found a perfect fit between Moses’ feminine hand and the glove of Thanksgiving. Indeed, it was a woman who “invented” the holiday as we know it. While it may have seemed in 1940 that Thanksgiving had been celebrated continuously since the Pilgrims first landed, this was not so. Its history in the intervening centuries reveals ephemeral initiatives and periods of widespread disinterest. Although George Washington had twice proclaimed a day of Thanksgiving, Thomas Jefferson had actively condemned it. Then largely a religious observance, the day was officially adopted by the state of New York in 1817, for example, and by the state of Virginia in 1855.27 Were it not for the work of Sarah Josepha Hale, there likely would be no national holiday, nor would it have had such strong patriotic connotations.

In 1827, as editor of Boston’s Ladies Magazine, Sarah Hale began a one-woman campaign to have Thanksgiving celebrated across the nation. Today she would be described as an essentialist, one who believes that women are innately more moral than men. For over thirty years, she waged a passionate crusade for a national holiday, enjoining her country to express gratitude by sharing a meal together. She believed that this moral act of family solidarity would lessen the likelihood of civil war.30 Later, when she was the influential editor of Godey’s Ladies Book, her efforts finally prevailed. It was Abraham Lincoln who acceded to her petition and promulgated Thanksgiving Day three years after Anna Mary Robertson was born.

That the legal celebration of the holiday had been formalized only in 1863, helps explain a curious story that Moses told the New York Times Magazine in 1948 when she was asked to recall her first Thanksgiving. While professing the difficulty of the task—she had seen so many Thanksgivings—she nonetheless was able to bring her thoughts back to the year 1864. She recollected that one day, when her father was going to town to buy boots, he told her he would bring her back a red dress. In turn, she promised to be a good girl all day long:

But when candlelight came, Father came in from the flax mill, and said he could not get his Boots. Because it was Thanksgiving day, and the Stores were closed. I was heart broken, to think I did not get my red dress. I could not eat my supper. Mother said it was too bad as I had been a good girl, that day.31

A few days later, her Dad again went shopping and this time brought back a dress that “was not red, it was more of a brick red, or brown. I was awfully disappointed but said nothing, so I never got what I call a red dress.”32

The anecdote is interesting in at least two regards. The young Anna Mary was so taken with the exact color red fixed in her mind’s eye that she could not be satisfied with a neutralized version of the hue. Like the tale of the princess and the pea, which revealed royal sensitivity through a stack of mattresses, the little girl’s specialized desire bespeaks the particular eye of an artist.33 Too, once it is realized that her father’s trip into town occurred on the second instance of the newly legalized national holiday, it is more understandable that he might have been unaware or had forgotten that stores would not be open on that day.

Just as the New York press had been quick to forge a link between Moses and the seasonal festivities she frequently depicted in her paintings, the national news media followed suit. By the end of the 1940s, Moses had become “indisputably associated with certain traditional holidays,” as Jane Kallir has previously noted.34 It became standard practice for the media to run features on her work at Thanksgiving and Christmas.

In November 1950, during the Korean War, the cereal manufacturer General Mills issued an advertisement that reproduced the artist’s Catching the Thanksgiving Turkey. The accompanying copy harked back to the Gimbel’s ads of the preceding decade: “It’s true that the 90th Thanksgiving of Grandma Moses isn’t the happiest America has known. Yet despite the shadow that hangs over the world today, we in America have much to be thankful for. . . .”35 Grandma had become almost as much of an institution as the holidays themselves.

As her fame and popularity grew, so did the accolades bestowed upon her. They came from diverse quarters—the National Press Club cited her as one of the five most newsworthy women in 1950, and the National Association of House Dress Manufacturers honored her as their 1951 Woman of the Year. Along with a group of women in their twenties and thirties, Mademoiselle named Grandma Moses as a “Young Woman of the Year” in 1948, awarding the artist a Mademoiselle Merit Award “for her flourishing young career and the youth of her spirit.”36 She was the only recipient to say that marriage and a career could not mix, a fact that was noted by the New York press.37 Interestingly, this immiscibility was the emotional theme of Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger’s 1948 film The Red Shoes, about a ballerina fatally torn between her art and her life.

With comments such as those that she made to Mademoiselle, the untutored Grandma Moses may not seem the most natural choice as a role model for young women art students in mid-twentieth-century America. But who else was there? No other woman artist even approached her level of renown. As a celebrity, she disarmed and charmed potential detractors in countless interviews, in which she related:

/ didn’t have an opportunity to study art, . . . but if a thing seems right to me, I do it. Art is like the Bible. Everyone reads the Bible and has a different opinion. Everyone looks at pictures and has a different opinion, so I go on my own. 1 love bright colors so I use bright colors. I don’t know much about perspective and things like that. But I paint because I like to and I know what I want to paint.38

Philadelphia’s Moore College of Art awarded Moses an honorary doctorate in 1951. Established as the Philadelphia School of Design for Women in 1848, Moore College was the nation’s first school of design,39 and remained a school with no male students. Founder Sarah King Peter had decided to educate women, to provide a means for supporting themselves, “should the necessity occur,” as her friend, Godey’s Lady’s Book editor Sarah Hale had phrased it.40 Peter chose a design-arts curriculum in part because “these arts can be practiced at home, without materially interfering with the routine of domestic duty, which is the peculiar province of women.”41 Even after the fine arts were added in the ensuing decades, the school continued to offer a rigorous education in design.

In March 1951, a little more than a century after its founding, Moore College decided to award its first honorary doctorates. They singled out five individuals: Anna Mary Robertson Moses topped the list of four men who were civic leaders.42 It is not known if the impetus to include Moses originated with the celebrated Reginald Marsh, then head of Moore’s Department of Painting. Perhaps the idea came from Moore’s recently retired Dean Harriet Sartain, who had a long-standing commitment to women’s art education. Despite the fact that Moses was unschooled in her art, the school keenly understood the usefulness of the highly successful woman artist as a role model for its students, faculty, and staff.

Although she had initially indicated that she would attend the ceremony, Moses received her Doctor of Fine Arts degree in absentia. Due to a lingering cold, the artist remained in upstate New York, her daughter-in-law Dorothy journeying to Philadelphia to represent her. Moses gave her acceptance speech via a special telephone hookup. “Grandma Moses Regrets ‘Not Being with Girls’,” read the headline reporting the event in the Evening Bulletin. She expressed gratitude for the honor and mentioned that she would have enjoyed being at the school, “especially with the girl students.”43

Another Evening Bulletin article focused on the artist’s textile work. Days in advance of the Moore awards ceremony, five local department stores had featured displays of drapery fabrics reproducing her paintings. Two of the designs had been introduced the year before, but two were making their debut that week. Although the report did not say so, textile design has been a major offering at Moore since its founding. The newspaper account did emphasize the appropriateness of Moore’s award to Moses: “… the oldest woman artist will be awarded an honorary degree by … the oldest women’s art school in the country.”44

A third Evening Bulletin story previewed the award from a “human interest” angle. Describing the artist as “a little old lady with a fastidious knot perched on top of her head as if it belongs there, and nowhere else,” the writer Polly Platt recounted the well-known story of the artist’s discovery. Platt recycled such decade-old quotes from Moses as her expressed preference for her preserves over her paintings, and her initial and inimitable response to news that her creations were fetching four-figure prices, namely that the buyers were crazy. Platt’s feature also contained material she gleaned from a visit to the artist’s home. In response to a question about her process, Moses explained how she would shape a canvas with a saw to fit the frame she had chosen: “A picture without a frame is like a woman without a dress, in my way of thinking.”45 To the Victorian-reared artist, good girls were only presentable with dresses, and nice pictures were best presented with frames, which completed and contained their painted image.

In August 1949, LIFE magazine published a photo essay on Jackson Pollock, audaciously subtitled “Is he the greatest living painter in the United States?” Had the editors taken a poll in that year, it is likely that most Americans would have responded, “No, Grandma Moses is.” A quaint and homespun nonagenarian, blissfully inattentive to avant-garde developments, Moses painted accessible subjects that fed a national nostalgia for a simpler time in our history. In a world of postwar expansion and burgeoning technologies, here was a visual poet of rural America who could recall hearing about President Lincoln’s assassination. In the decade of the 1940s, this endearingly cheerful Grandma from New York State managed to swallow the wolf of the male-dominated art world. At least for a time.

Notes

* Virtual bouquets are due to Rebecca Kelly, who cleared a path for me by working her way through the entire rich territory of the Grandma Moses scrapbooks, where most of the cited periodical clippings may be found; to Hildegard Bachert, an experienced hiker in this terrain; and to the indefatigable Traci Weatherford-Brown, for innumerable kindnesses as I processed what I found. Hildegard, Jane Kallir, and Rachel Stein offered valuable comments after reading an earlier draft of this essay.

1. Emory Lewis, “About New York,” Cue, January 1953.

2. The song, “Nobody’s Chasing Me,” was written for Out of This World.

3. Editorial, Allentown [Pennsylvania] Call, December 15, 1961.

4. Always fond of color, she once told reporters that she used to squeeze elderberry juice to dye otherwise drab dresses (Nancy Davids, “To Grandmother’s House We Go,” Collier’s Magazine, January 6, 1945, 48.

5. Ibid.

6. The Newark Star-Ledger, July 23, 1948.

7. Grandma Moses. 1946, quoted in Grandma Moses, promotional booklet published by Calhoun’s Collectors Society, Inc., 1980, title page (Grandma Moses Scrapbook, vol. 8, Galerie St. Etienne).

8. S. J. Woolf, New York Times Magazine, December 2, 1945.

9. Lucy R. Lippard, “Making Something from Nothing (Toward a Definition of Women’s ‘Hobby Art’),” first published in Heresies 4 (Winter 1978) and reprinted in her compilation of feminist essays on art, The Pink Glass Swan (New York: The New Press, 1995).

10. The sole mention of Moses in a feminist context is found in C. Kurt Dewhurst, Betty MacDowell, and Marsha MacDowell, Artists in Aprons: Folk Art by American Women (New York: E. P. Dutton, in association with the Museum of American Folk Art,

1979), 132, 166.

11. Interestingly, another self-taught “Grandma” did capture the attention of feminists in the 1970s, the living artist Grandma Tressa Prisbey. From 1958 to 1978, she made daily trips to the local dump in search of discarded bottles, automobile headlights, and other “treasures,” working alone without formal plans to fabricate 22 structures for her Bottle Village in Santa Susana, Simi Valley, California. Prisbey, a North Dakota transplant, began to build the miniature community when she was 60 years old. See Cynthia Carlson, “Grass Roots Art,” Ms., October 1977, 65. Grandma Prisbey’s 1975 exhibition at the Los Angeles Women’s Building was accompanied by a stapled catalogue, Grandma Prisbey’s Bottle Village, consisting of 14 pages of her own text, with photos by Irv Goodnoff and Mike Herman, printed by Dickranz Corporation.

12. Tribune reporter Carlyle Burrows, quoted in Art Digest, October 15, 1940.

13. This was probably an oblique reference to the concurrent exhibition by the black self-taught painter Horace Pippin, who was enjoying his own New York debut at the nearby Bignou Gallery. Pippin’s show ran through the middle of October. For

an account of that exhibition, see Judith E. Stein, “An American Original,” I Tell My Heart: The Art of Horace Pippin (New York: Universe, 1993), 20.

14. Howard Devree, New York Times, October 13, 1940, 10.

15. Emily Genauer, “The Galerie St. Etienne,” New York World-Telegram, October 12,1940, 10.

16. Ibid.

17. Galerie St. Etienne founder Otto Kallir credited the first published reference of “Grandma” to the Tribune (October 8, 1940), which noted: “Mrs. Anna Mary Robertson Moses, known to the countryside around Greenwich, New York, as Grandma Moses, began painting three years ago, when she was approaching 80” (quoted in Otto Kallir, Grandma Moses [New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1973], 26).

18. This and the following quotations are found in “Grandma Moses,” Art Digest, October 15, 1940.

19. Information given in a caption to a photo of the artist in the New York Post, November 15, 1940, 17.

20. These comments and the following description of the food table are from the New York World-Telegram, November 15, 1940.

21. Alice Graeme, “Rural Scenes by Anna Moses Have Flavor of Early U.S. Art,” a review (from an unidentified publication) of Moses’ January 1941 exhibition at the Whyte Gallery in Washington, D.C. (unpaged clipping, Grandma Moses Scrapbook, vol. I, Galerie St. Etienne).

22. A few months earlier, the New York Journal American had recounted the fate of Moses’ 1936 display of preserves and paintings at a fair in Cambridge, N.Y.: “For her strawberries she won a blue ribbon. For her painting she got no more than the razzberry!” (New York Journal American, October 8, 1940).

23. Eugenia Sheppard, New York Herald Tribune, November 14, 1945.

24. This example of Krasner’s conscious construction of her womanly identity is insightfully discussed by Anne Wagner in “Krasner’s Fictions,” Three Artists (Three Women) (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1996), 122.

25. “She Picked Up Her Paintbrush at Seventy-Seven,” Harper’s Bazaar, December 1942, 42.

26. Robert M. McCain, “She Took Up Art at 76,” The Woman with Woman’s Digest, May 1943, 18.

27. The Pathfinder (after December 1943).

28. Eleanor Early, “Just a Mother,” True Confessions, May 1947, 47.

29. RobertJ. Myers, Celebrations: The Complete Book of American Holidays (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1972), 278-80.

30. Frank N. Magill (ed.), Great Lives from History, American Women Series, vol. 3 (Pasadena, CA: Salem Press, 1995), 799.

31. Grandma Moses, “My First Thanksgiving,” New York Times Magazine, April 14, 1996, 91; originally appeared in issue of November 21, 1948 (artist’s punctuation).

32. Ibid. Eighty-four years later, she could still recall her unfulfilled desire and draw a moral for her readers: “I have found in after years it is best never to complain of disappointments, they are to be.”

33. Moses’ early sensitivity to color is also revealed in the anecdote about the candy-pink house that she related to Nancy Davids in the 1940s (see notes 4 and 5 above).

34. Jane Kallir, Grandma Moses: The Artist Behind the Myth (New York: Clarkson N. Potter, 1982), 19.

35. Advertisement in the New York Herald Tribune, November 19, 1950.

36. Mademoiselle, December 30, 1948.

37. New York Post, December 30, 1948.

38. McCain, “She Took Up Art at 76” (see note 26 above).

39. For the early history of the school, see Judith Stein, “The Genesis of America’s First School of Design: The Philadelphia School of Design for Women,” 1976, unpublished paper (in the library of Moore College of Art and Design).

40. Sarah Josepha Hale, “Editor’s Table,” Godey ‘s Lady’s Book 48 (March 1854): 271. She was of the opinion “that every young woman should be qualified by some accomplishment which she may teach, or some art or profession she can follow, to support herself creditably, should the necessity occur” (emphasis added).

41. Sarah King Peter [ca. 1850], quoted in Bruce Sinclair, Philadelphia’s PhilosopherMechanics: A History of the Franklin Institute (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1974), 3.

42. The other recipients listed behind Moses’ name on the program were: Edward Hopkinson Jr., an investment banker who was chairman of the City Planning Commission; Leroy Edgar Chapman, a doctor and state senator; Israel Stiefel, a state senator; and Henry Klonower, a Pennsylvania educator.

43. Grandma Moses, quoted in Gertrude Benson, “Grandma Moses Regrets ‘Not Being with Girls’,” Evening Bulletin, March 16, 1951, (unpaged clipping, Archives of Moore College of Art and Design).

44. Barbara Barnes, “Grandma Moses Sees Her Work Enter Textile Field,” Evening Bulletin, March 12, 1951, (unpaged clipping, Archives of Moore College of Art and Design).

45. Polly Platt, “A Little Old Lady of 90, Grandma Moses, Due for Philadelphia’s Homage This Week,” E vening Bulletin, March 11, 1951, (unpaged clipping, Archives of Moore College of Art and Design).