Published in the Exhibition Catalog for (re)FOCUS: Then and Now, on view at The Galleries at Moore through March 16, 2024

Fifty years ago, I was among a posse of Philadelphia feminists determined to rebalance an off-kilter art world. The villain? Patriarchal privilege. Our group of artists, teachers, and curators were “mad as hell and not going to take [it] anymore.”1 Why were there no women artists in our seminal art history texts? Why did museums rarely show or acquire art by women? Except in the “insignificant” fields of prints and textiles, why were there so few women curators? How could it be that while women made up the majority of art students, their teachers were overwhelmingly male?

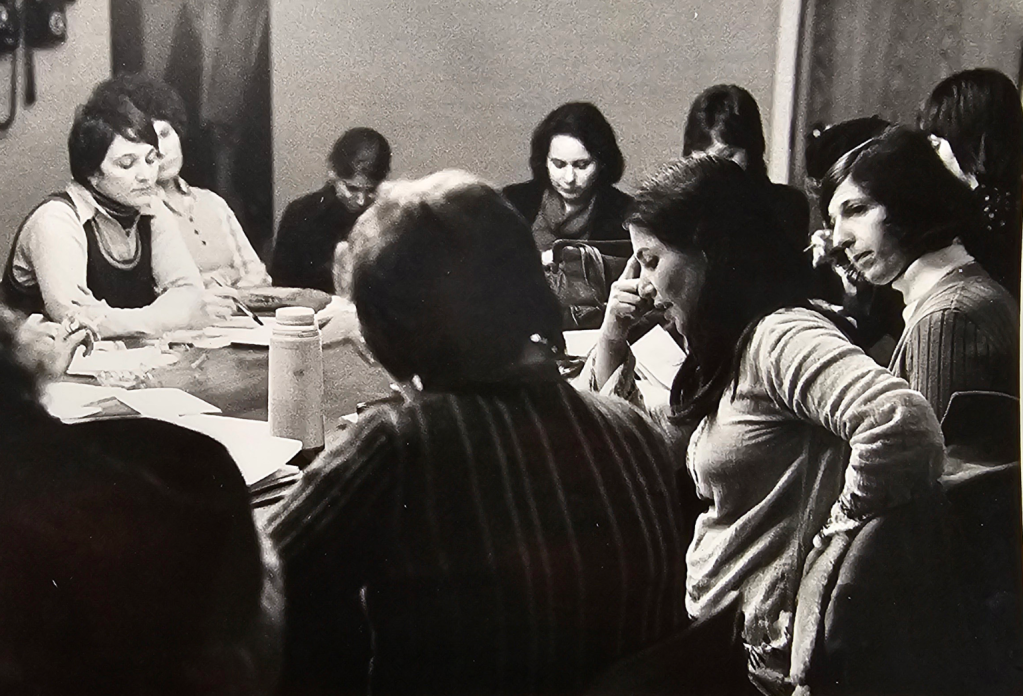

We’d all experienced the “click of recognition,” the moment, as Ms. Magazine described it, when one “suddenly and shockingly perceived the basic disorder in what has been believed to be the natural order of things.”2 To expand awareness of the sociocultural forces restricting women in the arts, in the spring of 1974, we carpet bombed the city with a three-month-long series of more than 150 women-centered exhibitions, panels, lectures, workshops, demonstrations and films. We called the initiative “FOCUS: Philadelphia Focuses on Women in the Visual Arts.”

The nervy title of its keystone exhibition, Woman’s Work: American Art 1974, flipped the meaning of the phrase traditionally used to describe handiwork of minimal importance. The majority of the 81 artists featured in this wide- ranging survey of current art was represented by more than one work. They included second generation abstract expressionists; color field painters; pop, minimalist, conceptual and performance artists; as well as contemporary landscapes, still lives and figuration. So diverse was the art on view, it’s unlikely that anyone who skipped reading labels would have guessed that men were missing from the mix.

It was installed at the Museum of the Philadelphia Civic Center, a spacious, if unconventional, venue for art. A decade earlier, the Beatles had performed at the Center on their first American tour. Now it was our turn to attract attention. Woman’s Work drew an enthusiastic audience who came to see what the New York Times called “a smashing contemporary display” that was “one of the best group shows of work by artists of any gender recently seen on the East Coast art circuit.”3

Of all the artists invited to participate, only one declined. Unfortunately, no record of her name survives. Perhaps it was Georgia O’Keeffe, then well into her eighties, who already had rebuffed Judy Chicago’s proffered sisterhood. O’Keeffe’s disinterest in women-only exhibitions is best understood from the vantage of the 1920s, when overt sexism streaked the arts like chocolate swirls in marble cake. O’Keeffe would have been familiar with the views of the popular, mid-Western art critic, C.J. Bulliet, who believed that “women painters . . . had gone far in imitation but have not had the initiative or the ability to blaze new paths for themselves.”4

*

A feminist, Gloria Steinem said, was “anyone who recognizes the equality and full humanity of women and men.” Such truths found no foothold in the press, which often stereotyped feminist activists as man-hating harpies who immolated their unmentionables. Small wonder that during FOCUS we occasionally encountered women who would disclose, “I’m not a feminist, but. . . .” Their “but” offered an opening for conversation. The not-feminists of the 1970s were sympathetic to our efforts to combat sexist injustice. They weren’t updated versions of the anti-feminists who’d opposed women’s suffrage. And, like us, they would have laughed to learn that nineteenth- century nay-sayers had opposed women’s higher education because, they were sure, college girls’ brains would siphon blood from their reproductive systems and thereby imperil the human race.

Why did those of us who organized FOCUS have no problem with labels? In large part, we considered ourselves to be trailblazers who understood that activism was a necessary step towards changing the status quo. While some of us had participated in the civil rights movement, others were veterans of anti-war demonstrations and Ban the Bomb protests. In our various experiences in the art world, all of us had encountered sexism, be it blatant or subtle.

There was no litmus test for feminism for the artists in Woman’s Work, many of whom distanced their worldviews from their art. Others wore their hearts on their sleeves, evidenced by their affection for non-traditional materials or subjects. At the time of Woman’s Work, film theorist Laura Mulvey was on the threshold of publishing her provocative, soon-to-be influential texts on the gendered gaze. It’s not known if Mulvey saw the exhibition, but if she had, the freshly envisioned erotic images by Marcia Marcus and Sylvia Sleigh would have held special interest.

In Marcus’s audacious Double Portrait (1972–3), she’s the middle-aged woman in a transparent nightgown who leans against her young male lover, “a tender, fair-haired flower child,” in art historian Linda Nochlin’s description. Aware they’re on display, the wary couple responds to our scopophilic gaze by eyeing us in return. The six male nudes in Sleigh’s arresting Turkish Bath (1973), embody a smile-provoking sendup of the voluptuous women in painted fantasies by Ingres and Titian. Depictions of a favored young model in two different poses bracket Sleigh’s ensemble of four actual art critics, one of whom is her husband, Lawrence Alloway, arranged like a classic odalisque.

Diverse manifestations of feminist content enriched Woman’s Work. Kitchen-savvy painter Janet Fish plundered the translucent treasures sheltering in jars of honey preserves. Faith Ringgold, the daughter of a dress designer and quilt maker, intertwined her art and passion for social justice. African-inspired masks supplanted faces in the two soft cloth sculptures on view from her Family of Women Mask series. Pat Lasch, whose mother was a seamstress and father a pastry chef, showed two abstract tondos made with muslin fabric punctuated with stitches of metallic thread. Lasch’s practice would shift a year after FOCUS, when she began her signature series of fantastical sculptured cakes “decorated” with acrylic paint extruded through pastry tubes.

The mid-seventies was a time of transition for other women artists who’d garnered early recognition as feminists. It’s revelatory to learn that Barbara Kruger, the conceptual artist and collagist, internationally known for her work with text and repurposed photographs, had a radically different practice in 1973. Although she was not represented in FOCUS, she did participate in that year’s Whitney Biennial, where she showed 2 A.M. cookie (Big), (1973), a nearly six feet wide, unframed circular composition on linen, made with acrylic, fur, cotton, stuffing, and glitter on embroidered fabric.

In the 1950s, New York’s uptown art galleries considered young Americans unworthy of attention, be they male or female. With nowhere to show their art, they created a cluster of viable cooperative galleries downtown. But most had shut down by the early 1960s, as commercial galleries began to take an interest in the younger generation. Regardless, women artists had a tougher time than men in finding gallery representation. To meet this need, two cooperative galleries founded by and for women opened in Manhattan in the early seventies: the A.I.R. Gallery in 1972 and SOHO 20 the following year. Of the 81 exhibitors in Woman’s Work, six were founding members of A.I.R.— Judith Bernstein, Blythe Bohnen, Agnes Denes, Pat Lasch, Howardena Pindell, and Barbara Zucker—and Sylvia Sleigh helped create SOHO 20. Yet there was no guarantee the coop members’ work would be taken seriously just because they had gallery representation. Lasch, who belonged to A.I.R. for a decade, recalled a critic saying to her, “Why are you showing in a women’s gallery? You’re too good for that.”5

Definitions of feminism continued to evolve in the decades since FOCUS. Some artists and academics later devalued feminist art per se as “essentialist,” meaning they consciously used techniques, materials, and imagery associated with women. Subsequent generations of artists expanded the meaning of feminism to encompass intersecting concerns about race, class, forms of privilege, and gender identity and fluidity. Just as granddaughters may enjoy a bond with their grandmothers that differs from their connection with their mothers, there were feminist artists in the nineties whose work allied more closely with art of the seventies than to the eighties.

Eleanor Antin’s Carving: A Traditional Sculpture (1972) was one of the most cheeky contributions to Woman’s Work. In her grid of sequential photographs of her own nude body during thirty-seven days of dieting, Antin gave truth to her title by “carving” off ten pounds to create a subtractive sculpture. When Antin exhibited Carving in Philadelphia, Janine Antoni was only eight years old. Yet when Antoni gained recognition an artist in the early 1990s, her work sometimes winked at her feminist predecessors. In her performance piece Loving Care (1993), Antoni dipped her tresses in hair dye to swish expressive strokes on the floor. Not only was her use of her own body as an art material akin to Antin’s, but it also poked fun at Jackson Pollock’s brag that he painted with the brush between his legs. Although she acknowledges the importance of the women artists of the 80s to her art, Antoni told an interviewer that “the irony of the 80s is not something I’m interested in. My strategy has more to do with the feminist artists of the 70s— the humor, the process, the emphasis on performance, the intensely visceral quality of their work.”6

*

The sixties weren’t far behind us when the FOCUS team chose to spotlight sexism’s ubiquitous presence by celebrating women’s achievements in the arts. We believed that separatism was justifiable, one step—the first one—towards equality. We hoped that our collective action would unleash the exponential energy needed to create change. Invigorated by the communal currents of feminism, we were undeterred by the enormity of our mission. Although we felt confident that sexism’s multiple manifestations in the art world would progressively fade, we couldn’t have predicted when it would happen. But any overly optimistic assessment of progress on our part was cut down to size by the work of the Guerrilla Girls in New York, founded in the 1980s. By harnessing simple statistics to the subversive power of humor, they showed—and continue to show—that although “we’ve come a long way, baby,” as Loretta Lynn sung in 1978, we’re far from arriving where we want to be.

- Lumet, Sidney, director. Network. United Artists, 1976. ↩︎

- O’Reilly, Jane. “click! The housewife’s moment of truth.” Ms., Spring 1972. ↩︎

- Glueck, Grace, “In Philadelphia, Sisterly Love.” New York Times, May 26, 1974. ↩︎

- Bulliet, C.J. Apples and Madonnnas. Chicago, Pascal Covici, 1927, pp. 137-39. ↩︎

- Stoller, Terry and Pat Lasch. “Pat Lasch: Sculptor.” Profiles in Art. Westbeth: home to the arts. July, 2021. https://westbeth.org/profiles-in-art/pat-lasch-sculptor/ Accessed December 22, 2023. ↩︎

- Cottingham, Laura and Janine Antoni. “Janine Antoni: Biting Sums Up my Relationship to Art History.” Flash Art, Summer 1993, p. 104. ↩︎